With dreams of Mars on the minds of both NASA and Elon Musk, long-distance crewed missions through space are coming. But you might be surprised to learn that modern rockets don’t go all that much faster than the rockets of the past.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

With dreams of Mars on the minds of both NASA and Elon Musk, long-distance crewed missions through space are coming. But you might be surprised to learn that modern rockets don’t go all that much faster than the rockets of the past.

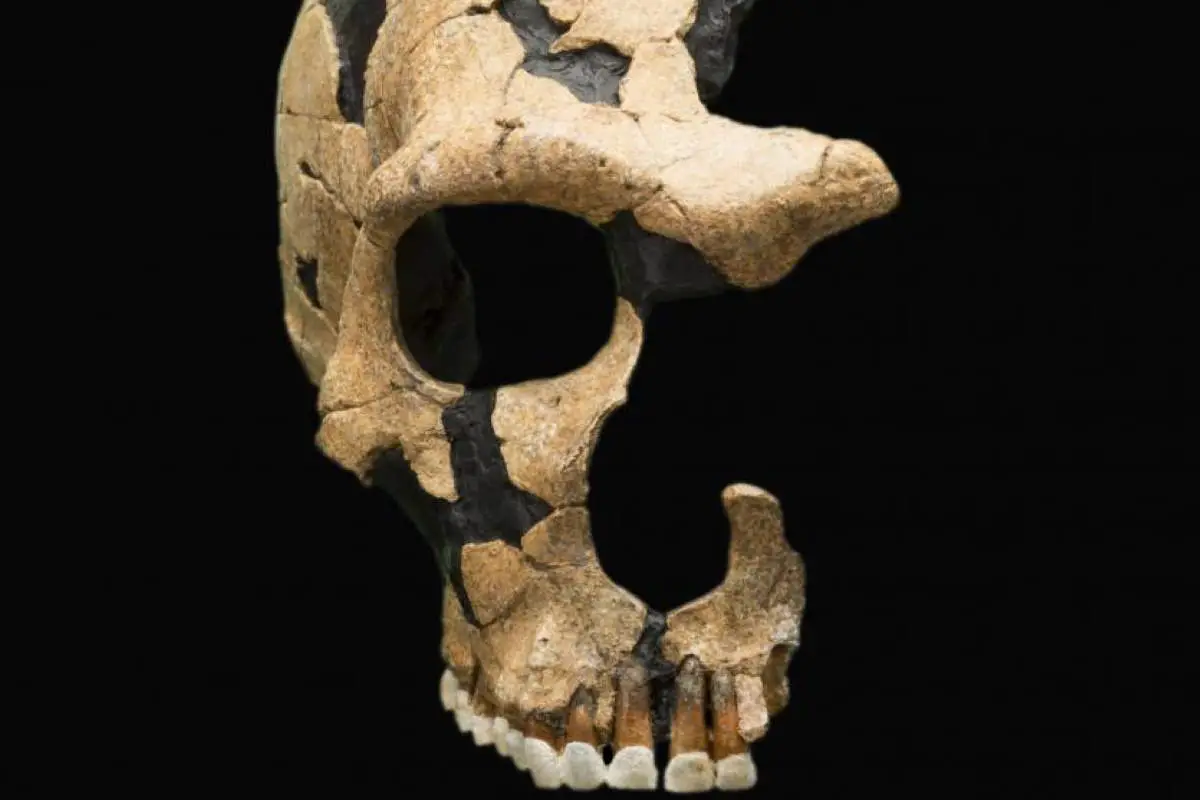

Will our species go extinct? The short answer is yes. The fossil record shows everything goes extinct, eventually. Almost all species that ever lived, over 99.9%, are extinct.

Some left descendants. Most – plesiosaurs, trilobites, Brontosaurus – didn’t. That’s also true of other human species. Neanderthals, Denisovans, H. erectus all vanished, leaving just H. sapiens. Humans are inevitably heading for extinction. The question isn’t whether we go extinct, but when.

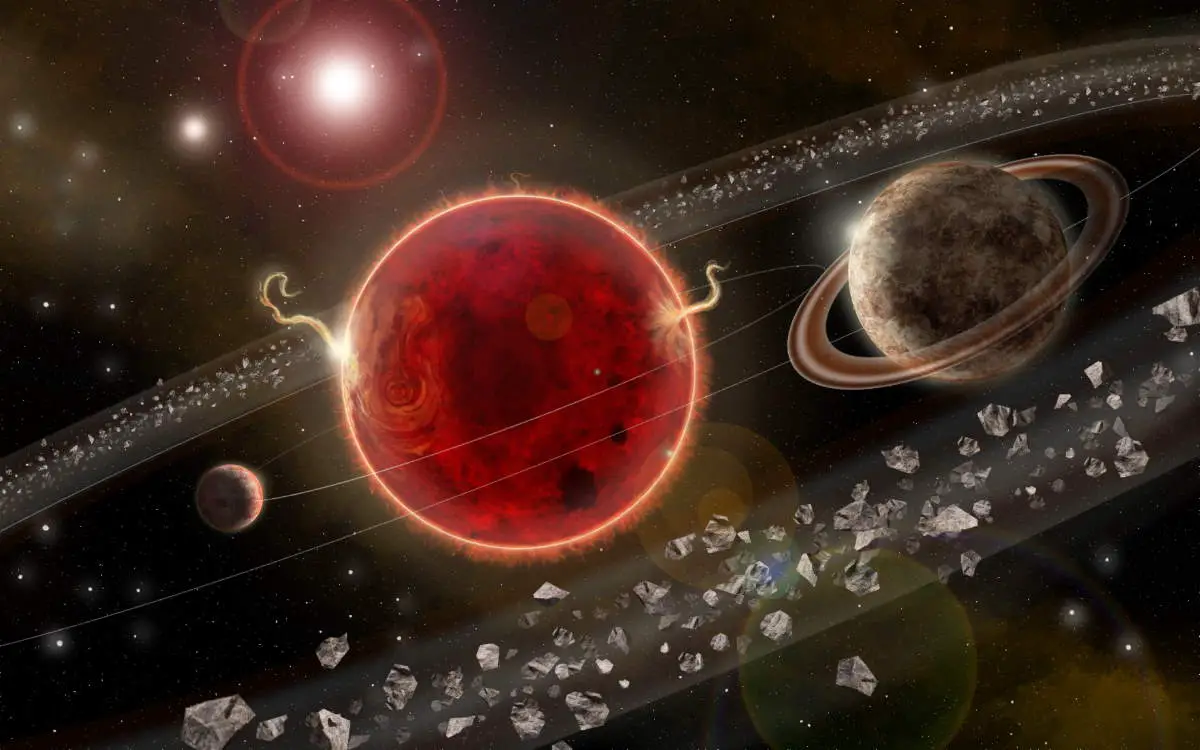

All stars emit varying amounts of light over time – and the Sun is no exception. Such changes in starlight can help us understand how habitable any planets around other stars are – a very active star may bombard its planets with harmful radiation. Now a new study, published in Science, shows that the Sun is significantly less active than other, similar stars.

Life is the last thing you would associate with the eternally dark craters of the lunar poles. But these craters could hold the key to explaining how complex, multi-cellular organisms evolved on Earth hundreds of millions of years ago, affording unimaginable insights into our planet’s biological past.

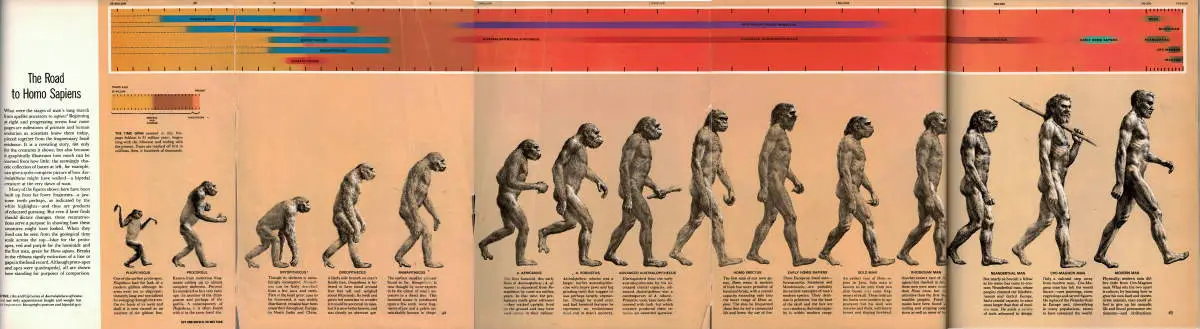

Evolution explains how all living beings, including us, came to be. It would be easy to assume evolution works by continuously adding features to organisms, constantly increasing their complexity. Some fish evolved legs and walked onto the land. Some dinosaurs evolved wings and began to fly. Others evolved wombs and began to give birth to live young.

Why the night sky is dark? It sounds obvious. That’s what night is. The sun has set and when you look up at the sky, it’s black. Except where there’s a star, of course. The stars are bright and shiny.

Most exoplanets, bodies orbiting stars other than the sun, are too far away for us to be able to send probes to. So it’s no wonder that the discovery of a possibly habitable planet around the sun’s nearest neighbour star, Proxima Centauri, a few years ago generated a lot of excitement. Now we have spotted what we think is a second planet around this star.

Every season has its characteristic star constellations in the night sky. Orion – one of the most recognisable – is distinctly visible on crisp, clear winter nights in the northern hemisphere. The constellation is easy to spot even in light-polluted cities, with its bright stars representing the shape of a person.

Betelgeuse, marking Orion’s top left shoulder, is often its brightest star. Red in colour, this star is usually the 12th brightest in the entire sky. But it has recently dimmed dramatically to an all-time low of the 21st brightest star in the sky. As a result, many have started speculating about whether it could be about to explode. But could it? And what would that look like?

For most people, continents are Earth’s seven main large landmasses.

But geoscientists have a different take on this. They look at the type of rock a feature is made of, rather than how much of its surface is above sea level.

In the past few years, we’ve seen an increase in the discovery of lost continents. Most of these have been plateaus or mountains made of continental crust hidden from our view, below sea level.

Maria Seton, University of Sydney; Joanne Whittaker, University of Tasmania, and Simon Williams, University of Sydney

Nine human species walked the Earth 300,000 years ago. Now there is just one. The Neanderthals, H. neanderthalensis, were stocky hunters adapted to Europe’s cold steppes. The related Denisovans inhabited Asia, while the more primitive H. erectus lived in Indonesia and H. rhodesiensis in central Africa. Were other humans the first victims of the sixth mass extinction?