Step back in time and delve into the awe-inspiring world of Earth’s largest prehistoric mammals. These colossal creatures, which once roamed the ancient landscapes, captivate our imaginations with their sheer size and extraordinary adaptations. From towering herbivores to formidable carnivores, the fossil record holds evidence of these titans of the past. Unearthed marvels that defy our present-day reality, these magnificent beings offer a glimpse into a bygone era of our planet’s history. Join us on a journey to discover the captivating tales of these ancient giants and unlock the secrets of their remarkable existence.

After the extinction of the dinosaurs, approximately 66 million years ago, the rise of mammals has begun. There were mammals on earth before that date, but after the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction event (a mass extinction of some three-quarters of the plant and animal species on Earth, including all non-avian dinosaurs), mammals took over the medium- to large-sized ecological niches. Some of these mammals reached enormous sizes, and usually, they were larger than today’s counterparts (with the exception of whales). Here are some of the largest prehistoric mammals ever known.

List of Largest Prehistoric Mammals

The largest primate ever lived: Gigantopithecus blacki

Gigantopithecus is an extinct genus of apes that lived from perhaps nine million years to as recently as one hundred thousand years ago, during the Miocene to Pleistocene epochs, in what is now India, Vietnam, China, and Indonesia. The genus contains three species: Gigantopithecus blacki, Gigantopithecus bilaspurensis, and Gigantopithecus giganteus.

Of these, Gigantopithecus blacki, which lived in what is now China and Vietnam, is the best-known. This creature was enormous compared to other primates. Based on the size of the few available jawbone fossils and a large number of teeth, scientists estimate that Gigantopithecus blacki stood up to 3 meters (9.8 feet) tall and could have weighed as much as 300 kg (660 lb), making it the largest known member of the primate family.

Despite its size, Gigantopithecus’s diet likely consisted mainly of vegetation, including bamboo. The large, flat molars were well suited to grinding up plant material, and dental wear patterns suggest a diet of tough, fibrous food. There’s also some evidence to suggest it may have been a seasonal frugivore (fruit eater).

Gigantopithecus is known only from a small number of dental and mandibular remains. A complete skull or a full skeleton has never been found, which is why much about this creature, including its locomotion (whether it walked on two or four legs), remains a mystery. Some theories suggest that, due to its size, Gigantopithecus would have been a quadruped.

The reasons for the extinction of Gigantopithecus are not definitively known but might include climate change and/or competition with other species, including early humans.

Carnivores

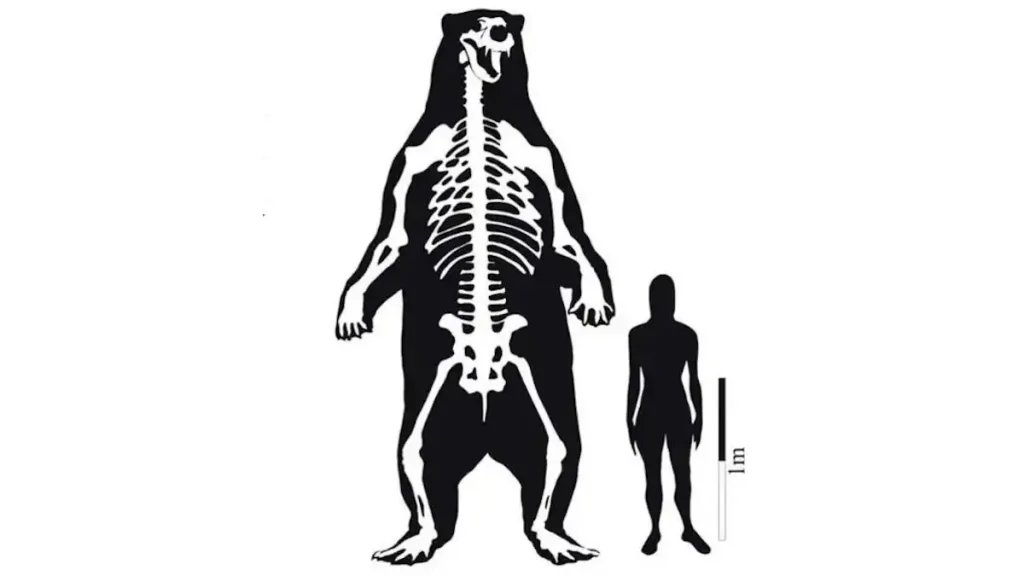

The largest carnivoran: South American short-faced bear [Arctotherium angustidens]

![Largest prehistoric mammals: Arctodus [short-faced bear]](https://cdn-0.ourplnt.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Arctodus-short-faced-bear-1024x683.webp)

The largest known terrestrial mammalian carnivoran of all time was (possibly) the South American short-faced bear (Arctotherium angustidens) (source 1 source 2). It lived during the Pleistocene epoch, approximately 2.5 million to 11,000 years ago, in what is now South America.

Arctotherium angustidens stood around 11 feet (3.4 meters) tall when standing on its hind legs and weighed an estimated 3,500 to 3,800 pounds (1,600 to 1,700 kilograms), making it larger than any living bear species today.

This prehistoric bear had a robust build with long limbs, allowing it to be an efficient walker and runner. It had a short face, hence its common name. The bear’s teeth were adapted for crushing and grinding tough vegetation. Arctotherium angustidens likely had a primarily herbivorous diet, feeding on plants, fruits, and roots.

The South American giant short-faced bear is believed to have been a solitary animal, capable of overpowering and hunting large prey if necessary, although its exact hunting habits are still debated among scientists. Fossil evidence suggests that Arctotherium angustidens coexisted with other large mammals, such as giant sloths and saber-toothed cats, in the ancient ecosystems of South America.

The extinction of Arctotherium angustidens, like many other megafauna species, is thought to be related to climate change and human activities, including overhunting. Despite its massive size and intriguing adaptations, much of our knowledge about this extinct bear is based on fossil remains, making it a subject of ongoing scientific research and exploration.

Andrewsarchus

Previously, the Andrewsarchus was declared the largest terrestrial mammalian carnivore known on the basis of the length of the partial skull.

Andrewsarchus mongoliensis is an extinct mammal that lived during the Eocene epoch, approximately 45 to 36 million years ago. It is known from fossil remains found in Mongolia. Andrewsarchus is notable for its large size and unique anatomical features, making it a subject of fascination among paleontologists.

American paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn (August 8, 1857 – November 6, 1935), who named Andrewsarchus mongoliensis, believed it to be the largest terrestrial, carnivorous mammal: Based on the 83.4 cm (2.74 feet) length of the skull, and using the proportions of Mesonyx (an extinct prehistoric mammal), he estimated a total body length of 3.82 meters (12.5 feet) and body height of 1.89 meters (6.2 feet) at the shoulder.

However, considering cranial and dental similarities with entelodonts, Szalay and Gould proposed that it had proportions more like them than mesonychids and that Osborn’s estimates were inaccurate. Now, paleontologists are far more cautious about Andrewsarchus’ size as so far only the skull of this animal is known.

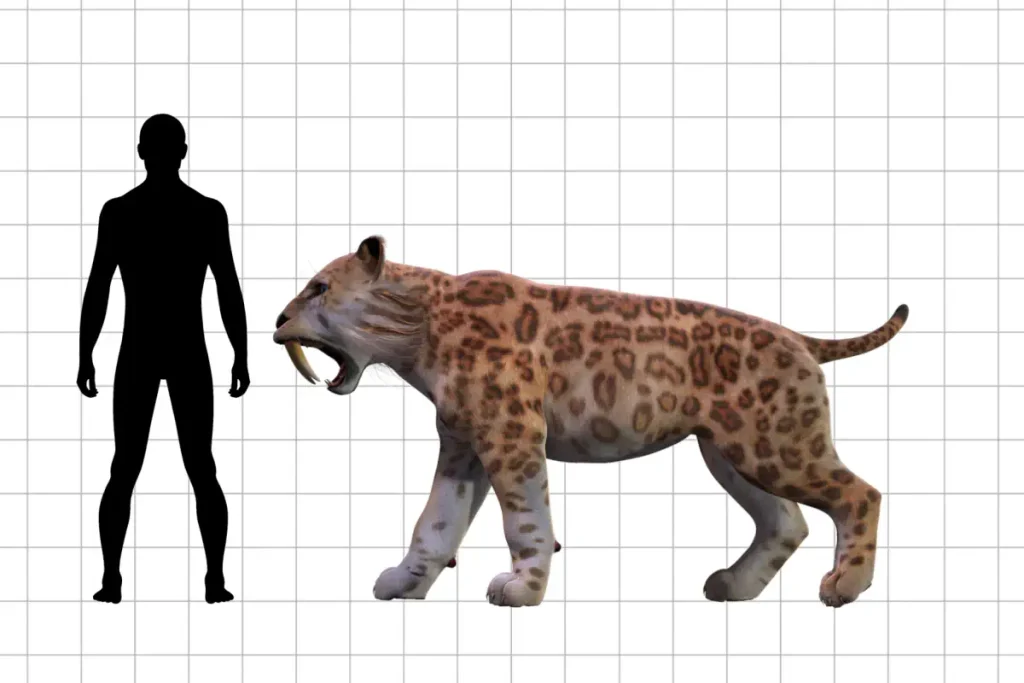

The largest prehistoric cat: Smilodon populator

The largest known prehistoric felid was the

Related: The largest prehistoric cats

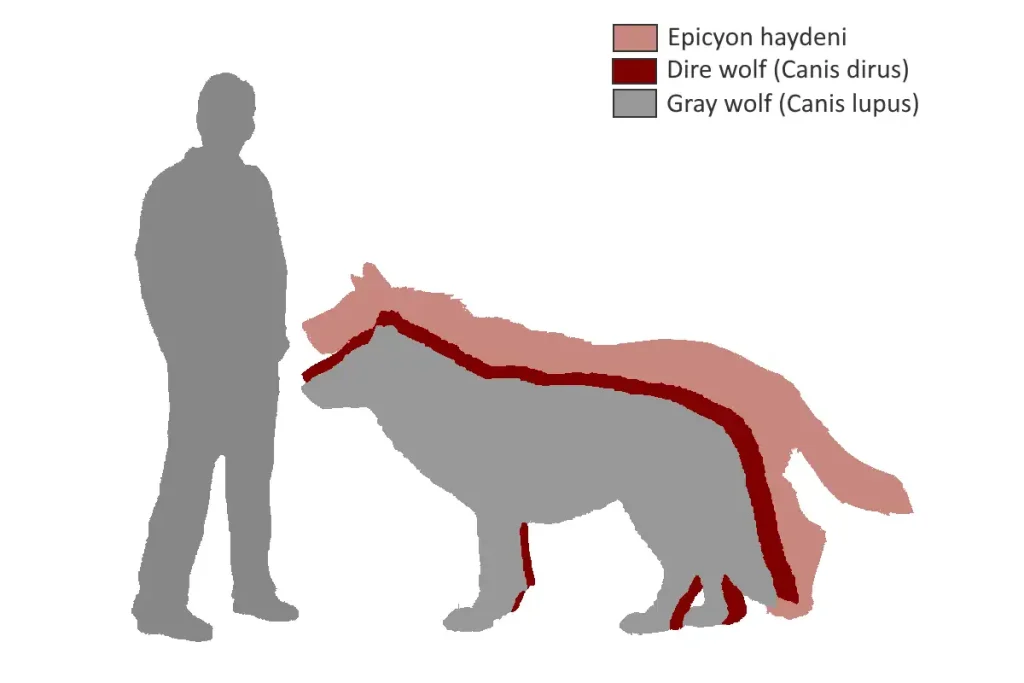

The largest prehistoric canid: Epicyon

The largest prehistoric canid (and the largest canid of all time) was Epicyon (“more than dog”), a genus of extinct canids, which are colloquially known as “bone-crushing” or “hyena-like” dogs. They existed during the Miocene epoch, approximately 20 to 5 million years ago, and are known for being among the largest predators of their time.

Epicyon was the largest genus among the subfamily Borophaginae. One species, Epicyon haydeni, is believed to have been the largest canine ever, with large individuals potentially weighing over 150 kg (330 lbs) and standing at a shoulder height of around 90 cm (35 inches).

It was even bigger than the dire wolf (Canis dirus, “fearsome dog”), the largest wolf ever roamed Earth.

These predators had robust skulls and powerful jaws, which enabled them to kill and consume large prey. Their teeth were built for crushing bone, a feature that distinguishes them from many other types of prehistoric dogs.

Their fossils have been found in various locations across North America. The disappearance of Epicyon, along with other large borophagines, is believed to coincide with the arrival of the first canines that are more similar to the dogs, wolves, and foxes we know today.

The largest bear dog: Pseudocyon

The largest “bear dog” was Pseudocyon (false dog). They inhabited Eurasia and North America during the Miocene epoch living approximately 5.3 million years. The largest fossil find was of a mandible (F:AM 49247) founded in New Mexico. The mass estimate derived from the mandible was about 773 kg, representing a very large individual.

Pseudocyon is a genus of extinct mammals from the family Amphicyonidae, otherwise known as “bear dogs”. Notably, they are not directly related to modern dogs or bears, but they shared some physical characteristics with both, hence the name.

The genus Pseudocyon includes several species, such as Pseudocyon ledouxi and Pseudocyon sansaniensis. They were carnivores, and their diet likely consisted of a variety of animals, including small mammals and possibly carrion.

These creatures were medium-sized with robustly built bodies. Their skeletal structure suggests they were likely very strong and capable predators. They possessed long limbs and might have been good runners, potentially capable of chasing down prey.

The largest hyena-cat: Simbakubwa

Simbakubwa kutokaafrika is an extinct species of mammal that lived during the Miocene epoch, approximately 22 million years ago. The name Simbakubwa means “great lion” in Swahili, but despite this name, the creature was not a lion nor was it closely related to felines. Instead, it belonged to a group known as hyainailourid hyaenodonts, which were among the first large mammalian predators in Africa.

Simbakubwa was an enormous predator. Estimates based on its fossils suggest it could have been larger than a polar bear, potentially making it one of the largest known terrestrial mammalian carnivores. However, more data would be needed to confirm this.

Unlike modern carnivores, Simbakubwa had a unique dental setup with different types of specialized teeth for different feeding strategies. This included long, blade-like carnassial teeth for slicing meat and strong front teeth that could have been used to capture and hold onto prey.

Fossils of Simbakubwa were discovered in Kenya, but they were initially misidentified and stored in a museum drawer for years. The species was not identified and named until 2019, highlighting how much there is still to learn about the history of life on Earth.

The species name Simbakubwa kutokaafrika means “great lion of Africa” in Swahili language.

The largest prehistoric hyena: Pachycrocuta

Pachycrocuta, commonly known as the giant short-faced hyena, is an extinct genus of hyenas. The most famous and largest species of this genus is Pachycrocuta brevirostris, which lived during the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs, roughly 3 million to 500,000 years ago.

This species is considered one of the largest hyenas to have ever lived. Adult individuals could reach lengths of up to 2 meters (6.5 ft) and stand about 1 meter (3.3 ft) tall at the shoulder. They could weigh up to 190 kg (420 lbs), making them significantly larger than modern hyenas.

Pachycrocuta brevirostris was a highly successful scavenger, with a wide geographic range that included parts of Asia, Europe, and Africa. It is best known for its large, powerful jaws and massive teeth capable of crushing bone. Its short, strong neck would have allowed it to exert a tremendous amount of force to break bones and extract marrow, a rich source of nutrients.

Pachycrocuta became extinct around the same time as many other large mammals, during a period of significant climate change at the end of the Pleistocene epoch. Some theories suggest that competition with the early human species for carrion could have also played a role in their extinction.

Ground sloths

Megatherium

Megatherium (from the Greek mega, meaning “great“, and therion, “beast“), commonly known as the giant ground sloth, is an extinct genus of ground sloths that lived in South America from the Early Pliocene to the end of the Pleistocene, around 5 million to 11,000 years ago. It was one of the largest land mammals known, exceeded in size among terrestrial mammals only by a few species of mammoths and elephants.

The typical Megatherium species, Megatherium americanum, could reach up to 6 meters (20 feet) in length, including the tail, and weighed as much as 4 tonnes. It was as big as modern elephants. The size and structure of its skeleton suggest it lived most of its life on the ground, but it was likely capable of bipedal locomotion, standing up on its hind legs to reach high vegetation.

Megatherium’s teeth were quite different from those of most mammals; they were simple and peg-like and lacked enamel. This kind of dentition suggests that Megatherium was a herbivore with a diet of coarse, fibrous plants or leaves. The large, sharp claws on its hands suggest it might have been able to pull branches down toward its mouth.

Evidence suggests that Megatherium could have coexisted with early humans in the Americas, and some hypotheses suggest that human hunting could have played a role in its extinction. Climate change at the end of the last ice age, causing shifts in vegetation patterns, could also have contributed to its extinction.

Even-toed ungulates

Hippopotamus gorgops

The largest known Even-toed ungulate (artiodactyl) was Hippopotamus gorgops with a length of 4.3 meters (14 feet) and a height of 2.1 meters (6.9 feet). With a weight of 3,900 kilograms (8,600 lb), it was much larger than its living relative, Hippopotamus amphibius. Today’s male hippopotamus adults average 1,500 kg (3,300 lb) in weight and they reach 1.5 meters (4.92 feet) at the shoulder.

Giraffe: the tallest ever even-toed ungulate

The tallest ever even-toed ungulate is not extinct: it is the giraffe. With a height of up to 5.7 meters (18.7 feet), the giraffe is also the tallest living terrestrial animal.

Odd-toed ungulates

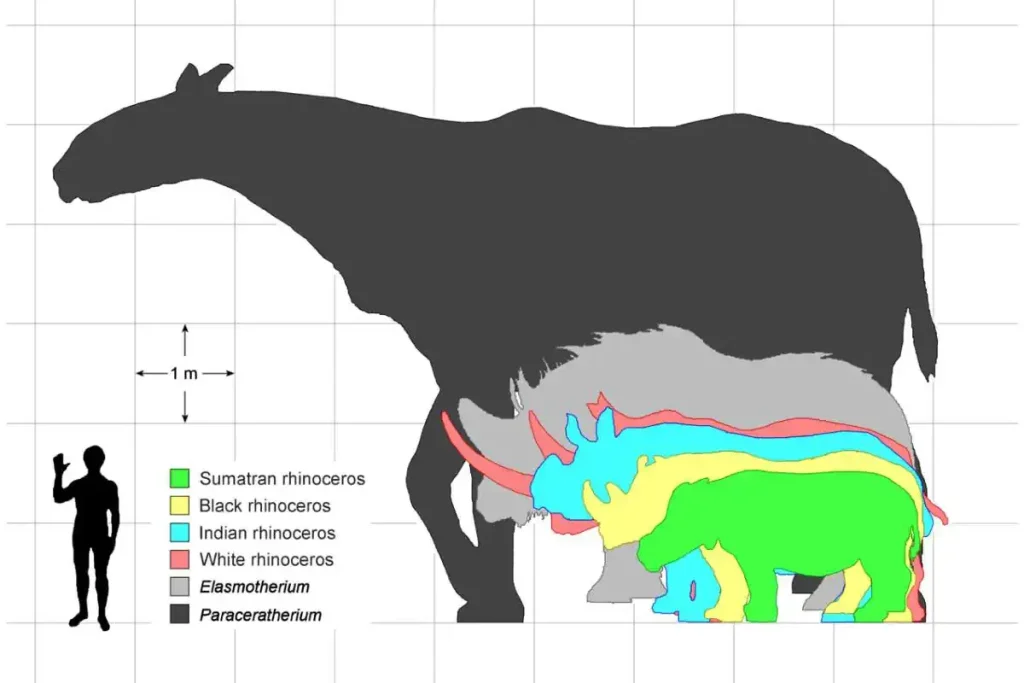

Paraceratherium

The largest known Odd-toed ungulate (perissodactyl), and the second-largest land mammal ever, was Indricotherium (also known as Paraceratherium).

Paraceratherium, also known as Indricotherium or Baluchitherium, is an extinct genus of hornless rhinoceros, and one of the largest terrestrial mammals that has ever existed. It lived during the Oligocene epoch, approximately 34-23 million years ago.

Paraceratherium’s remains have been found across Eurasia, between China and the Balkans. The animal was an enormous creature, standing up to 4.8 meters (16 feet) tall at the shoulder with a length of up to 7.4 meters (24 feet). When including its long neck and head, it’s estimated to have been about 5.5 meters (18 feet) tall. Its weight estimates vary but most range from 15 to 20 tonnes.

Despite being a member of the group that includes modern rhinos, Paraceratherium’s appearance was quite different due to its size and proportions. It had a long, slender skull, and a relatively long neck for a rhinoceros-like animal. Its limbs were long and column-like, similar to those of modern elephants.

Paraceratherium was a herbivore, and it likely used its height to reach and eat tall vegetation, somewhat similar to a modern-day giraffe. The shape and wear patterns of Paraceratherium teeth suggest they ate soft leaves and twigs rather than tough, fibrous grasses.

The reason for Paraceratherium’s extinction is not well understood. Climate change and the evolution of new types of vegetation that this creature could not eat are often suggested as factors.

Giant rhinoceros [Elasmotherium]

There was also a giant rhinoceros (Elasmotherium). It was a large mammal, almost the size of a mammoth. The known specimens of E. sibiricum reach up to 4.5 meters (15 feet) in body length with shoulder heights over 2 meters (6 feet 7 inches) while E. caucasicum reaches at least 5 meters (16 feet) in body length with an estimated mass of 3.6-4.5 tonnes (4-5 short tons).

Elephants, mammoths, and mastodons

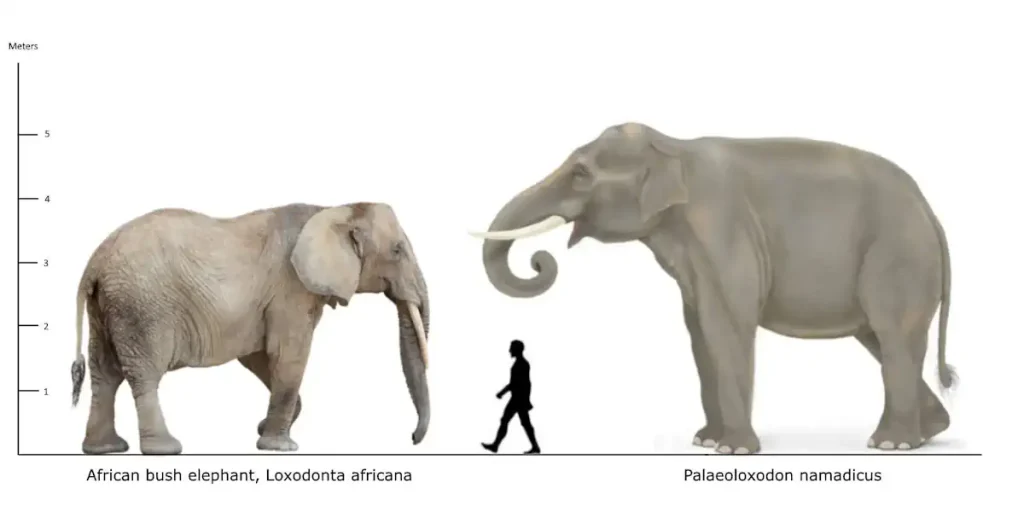

The largest land mammal ever: Palaeoloxodon namadicus

Palaeoloxodon namadicus, commonly known as the Asian straight-tusked elephant, is an extinct species of elephant that lived during the Pleistocene epoch. It is thought to have ranged across much of Asia, including India, Japan, and Sri Lanka.

The species is known for its size, being probably the largest land mammal that has ever existed. Some estimates suggest that males could reach a shoulder height of up to 5.2 meters (17 feet) and possibly weigh up to 22 tonnes, though these figures are based on fragmentary remains, so exact dimensions and weight are subject to debate.

The animal gets its common name from the long, straight tusks that were a defining feature of the species. It’s believed that these tusks may have been used in intra-species combat, similar to modern elephants, as well as for foraging.

Palaeoloxodon namadicus is a part of the genus Palaeoloxodon, a group of elephants that also included other straight-tusked elephants. The species was named by British paleontologist Hugh Falconer in 1857.

The extinction of Palaeoloxodon namadicus, like with many Pleistocene megafaunas, is not fully understood, but it is thought that a combination of climate change and overhunting by humans may have contributed to its demise.

The largest mammoth ever: the steppe mammoth

Among the giants that once walked the earth were the mammoth species, the southern mammoth (Mammuthus meridionalis), and its progeny, the steppe mammoth (Mammuthus trogontherii), standing as some of the largest creatures of their kind. The southern mammoth, known for its grand scale, roamed across the temperate climes of northern Eurasia, their presence dating back to approximately 2 million years ago. These colossal mammals, with their towering stature, left their footprints across the vast landscapes of the north, a testament to their once widespread existence.

Meanwhile, the steppe mammoth, a descendant of the southern mammoth, traces its origins back to the farthest reaches of northern China. The steppe mammoth made its appearance on the planet around 1.6 million years ago, subsequently spreading to other regions across Eurasia, extending its ancestral legacy. This particular species was even larger than its predecessor, with the largest documented specimen exhibiting a staggering shoulder height of 4.5 meters (14 feet 9 inches). The behemoth weighed in excess of 14 tonnes (equivalent to 15.4 US tons), highlighting the remarkable magnitude of these ancient mammals.

For comparison, the largest elephant ever recorded, an African bush elephant named Henry stood over 13 feet (3.96 meters) tall. He was about 11 tons in weight.

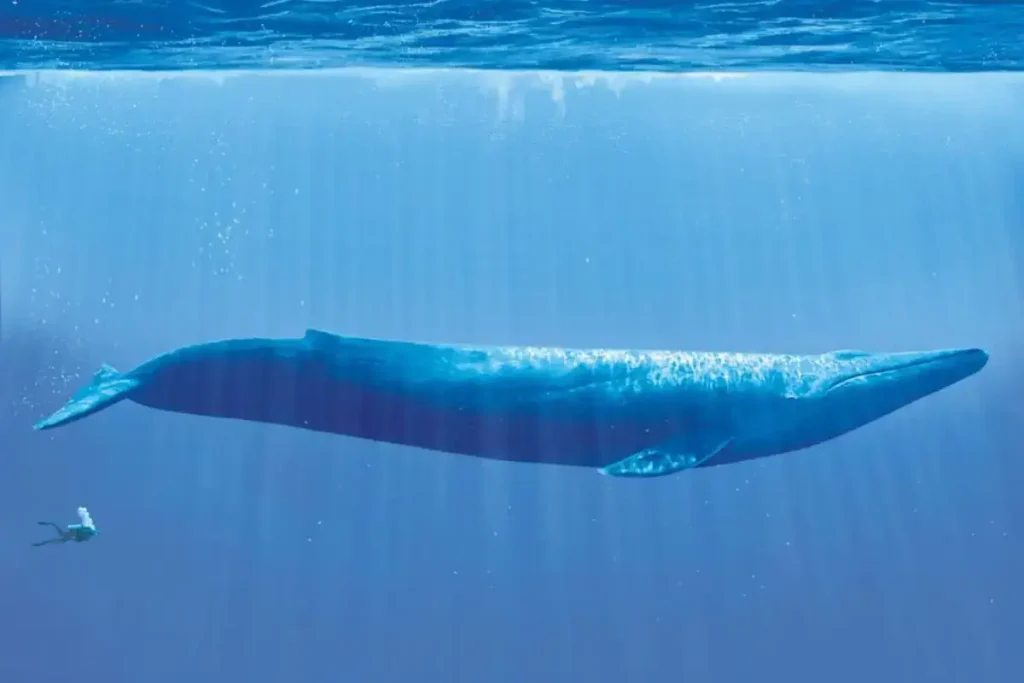

Whales

The extant blue whale is the largest and heaviest animal known to have existed, it is bigger than any animal that lived on Earth, including dinosaurs. They grow up to 112 ft (34 meters) in length and 190 tonnes (210 short tons) in weight.

Some Pliocene-age baleen whales (the Blue whale is also a baleen whale) were likely rivaled the modern blue whale in size – but they were still slightly smaller.

Related: Amazing Blue Whale Drone Footage

Sources

- Mammal on Wikipedia

- Largest prehistoric animals on Wikipedia

- Arctotherium on Wikipedia

- Epicyon on Wikipedia

- Pseudocyon on Wikipedia

- Pachycrocuta on Wikipedia

- Andrewsarchus on prehistoric-wildlife.com

- Elasmotherium on Wikipedia

- Megatherium on Wikipedia

- Simbakubwa on Wikipedia

- “Largest mammoth” on the Guinness World Records website

- Moon Landings: All-Time List [1966-2025] - February 2, 2025

- What Is Max-Q and Why Is It Important During Rocket Launches? - January 16, 2025

- Top 10 Tallest Rockets Ever Launched [2025 Update] - January 16, 2025

One reply on “Titans of the past: Largest prehistoric mammals that roamed Earth”

I have learnt something new. Great site!