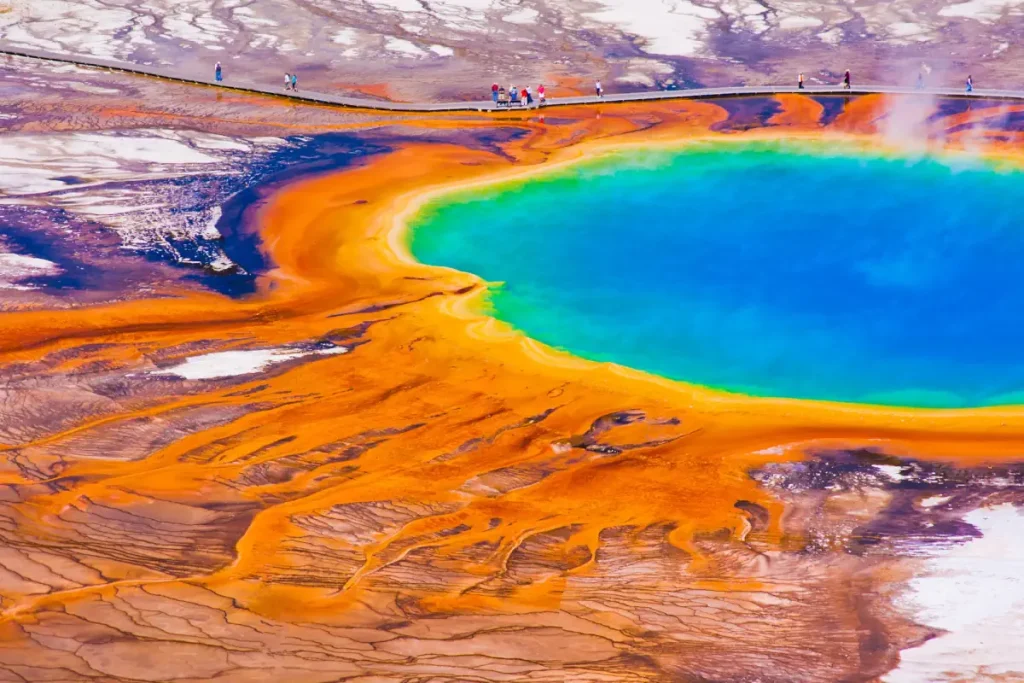

Yellowstone National Park, renowned for its geysers, also astonishes visitors with the vibrant colors accompanying these thermal features. Gazing upon these landscapes, one is treated to a visual feast of yellows, oranges, reds, and greens in the flowing hot water, the lining of hot pools, and even in the steam which can appear tinged with color.

The unique colors of Yellowstone have been noted since the early days of trappers and explorers and were also documented by the geologists mapping the thermal basins in the 1870s. A significant realization occurred in 1889 when geologist Walter H. Weed first identified that these colorful deposits were not mere mineral formations, but were actually microbial in nature.

The existence of life in water that is scaldingly hot is truly astonishing. What’s even more remarkable is that these organisms, known as thermophiles, not only survive but also flourish in these extreme conditions. They have evolved to be so specialized for high-temperature environments that they cannot exist elsewhere.

Thermophiles are found globally in various high-temperature environments such as volcanoes, deserts, and even man-made settings like power plants and hot water heaters. However, their presence is most striking and colorful in Yellowstone, offering a spectacular display unmatched anywhere else in the world.

What Makes Yellowstone’s Colors?

The colors of Yellowstone’s thermal features have long been a source of wonder. Osborne Russell (June 19, 1814 – May 1, 1884), a trapper in the Yellowstone region from 1834 to 1843, was among the first to record these colors in detail. Describing the Grand Prismatic Spring, he observed steam arising in distinct hues – white, pale red, and light sky blue, speculating about atmospheric conditions or chemical properties in the water.

A side note, Osborne Russell was a colorful character. He was a mountain man and politician who helped form the government of the U.S. state of Oregon.

The secret behind these colors lies in the combination of microbial life and the physics of light. In features like the Grand Prismatic Spring, the striking orange hues are due to pigmented bacteria in the microbial mats, while the vibrant blues result from the refraction of the skylight.

At the heart of photosynthesis is chlorophyll, which is inherently green. Yet, in Yellowstone, chlorophyll is often overshadowed by carotenoids, pigments related to vitamin A, and seen in colors ranging from orange to red. These carotenoids serve a protective function, shielding cells from intense sunlight, particularly prevalent during Yellowstone’s summers.

The observable color of these microbial mats largely depends on the balance between chlorophyll and carotenoids. In summer, when chlorophyll levels dip, the mats exhibit hues of orange, red, or yellow. Conversely, in winter, with less intense sunlight, chlorophyll becomes more dominant, turning the mats dark green. Even a spell of cloudy days in summer can increase chlorophyll concentration, leading to a noticeable darkening of the mats.

Therefore, the mesmerizing colors of Yellowstone are not just a product of the bacterial species present but are also a dynamic response to varying levels of sunlight throughout the year. This interplay of biology and environmental factors creates the park’s stunning and ever-changing thermal landscapes.

Sources

- Yellowstone National Park on Wikipedia

- Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone on Wikipedia

- “The Science Behind Yellowstone’s Rainbow Hot Spring” on the Smithsonian Magazine website

- Budget of NASA, Year by Year [1980-1989] - June 10, 2024

- Budget of NASA, Year by Year [1970-1979] - June 10, 2024

- Budget of NASA, Year by Year [1958-2024] - June 10, 2024