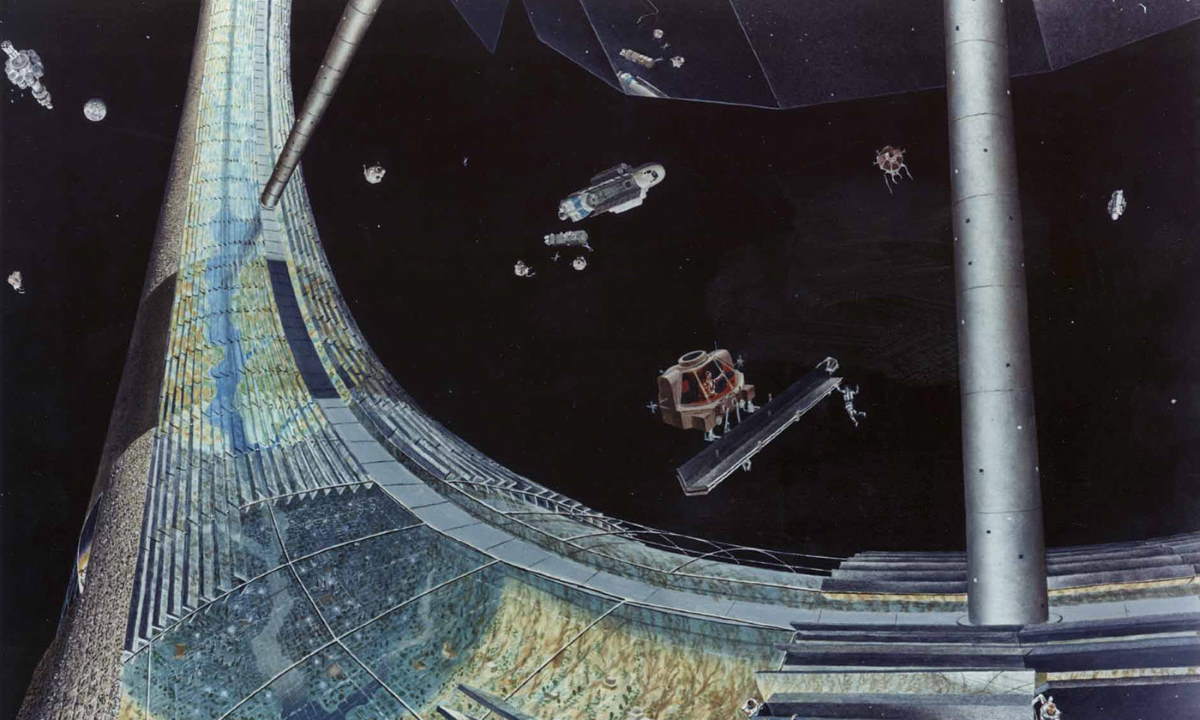

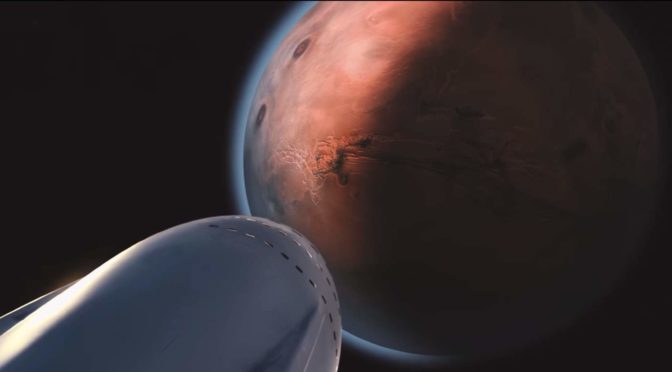

If human beings are ever to colonize other planets – which might become necessary for the survival of the species, given how far we have degraded this one – they will almost certainly have to use generation ships: spaceships that will support not just those who set out on them, but also their descendants. The …

Continue reading “Would it be immoral to send out a generation starship?”