NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft has technical problems, it is generating random-looking telemetry data, and as a result, the spacecraft doesn’t know where it is.

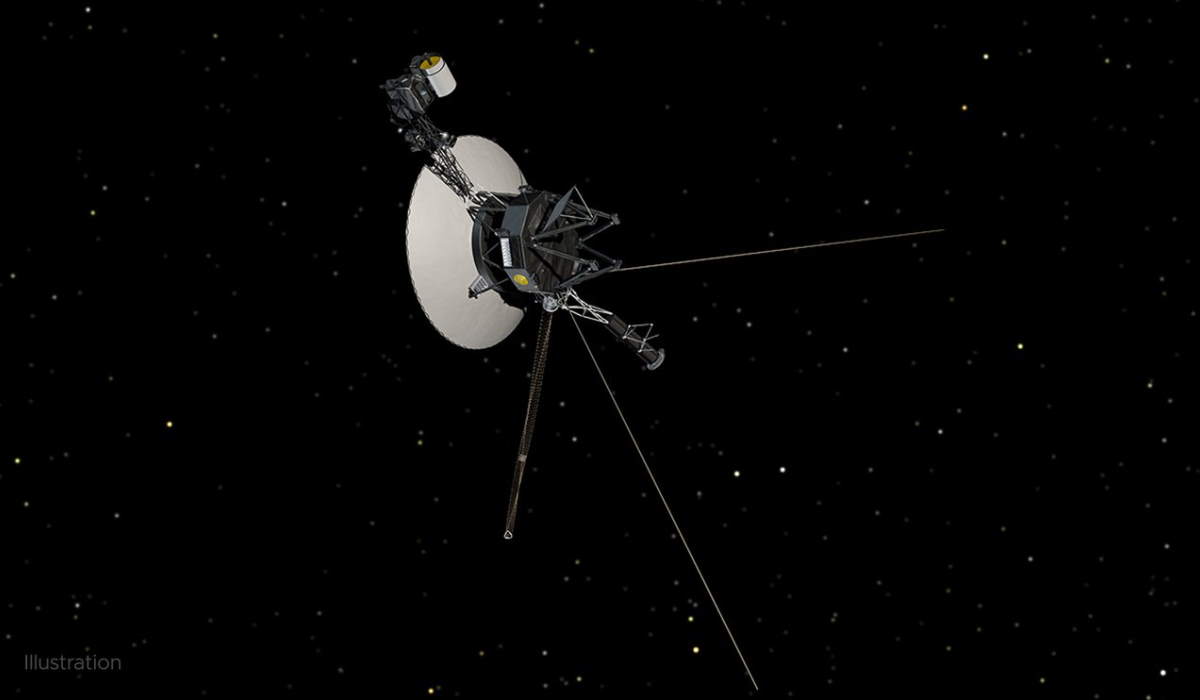

Old computer systems have a lot of wacky ways to fail. Computers that are constantly blasted by radiation have even more wacky ways to fail. Combine those two attributes, and eventually, you’re bound to have something happen. It certainly seems to have with Voyager 1. The space probe, which has been in active service for NASA for almost 45 years (it was launched on September 5, 1977, as part of the Voyager program to study the outer Solar System and interstellar space beyond the Sun’s heliosphere), is sending back telemetry data that doesn’t make any sense.

At this point in the probe’s journey, that’s surprisingly not that big of a deal. Telemetry data helps position Voyager’s science instruments and its high-gain antenna that allows it to talk to Earth continually. Both of those systems seem to still be in working order, as the data science instruments are sending back good readings, and those readings are getting to Earth, which shows that the antenna is still pointed in the right direction.

What might be causing this strange data is a mystery at this point. Engineers are trying to narrow down the problem. Their first step is to determine whether whatever is causing the randomized data is in the attitude and articulation control system (AACS) or some other sub-system that feeds data into it.

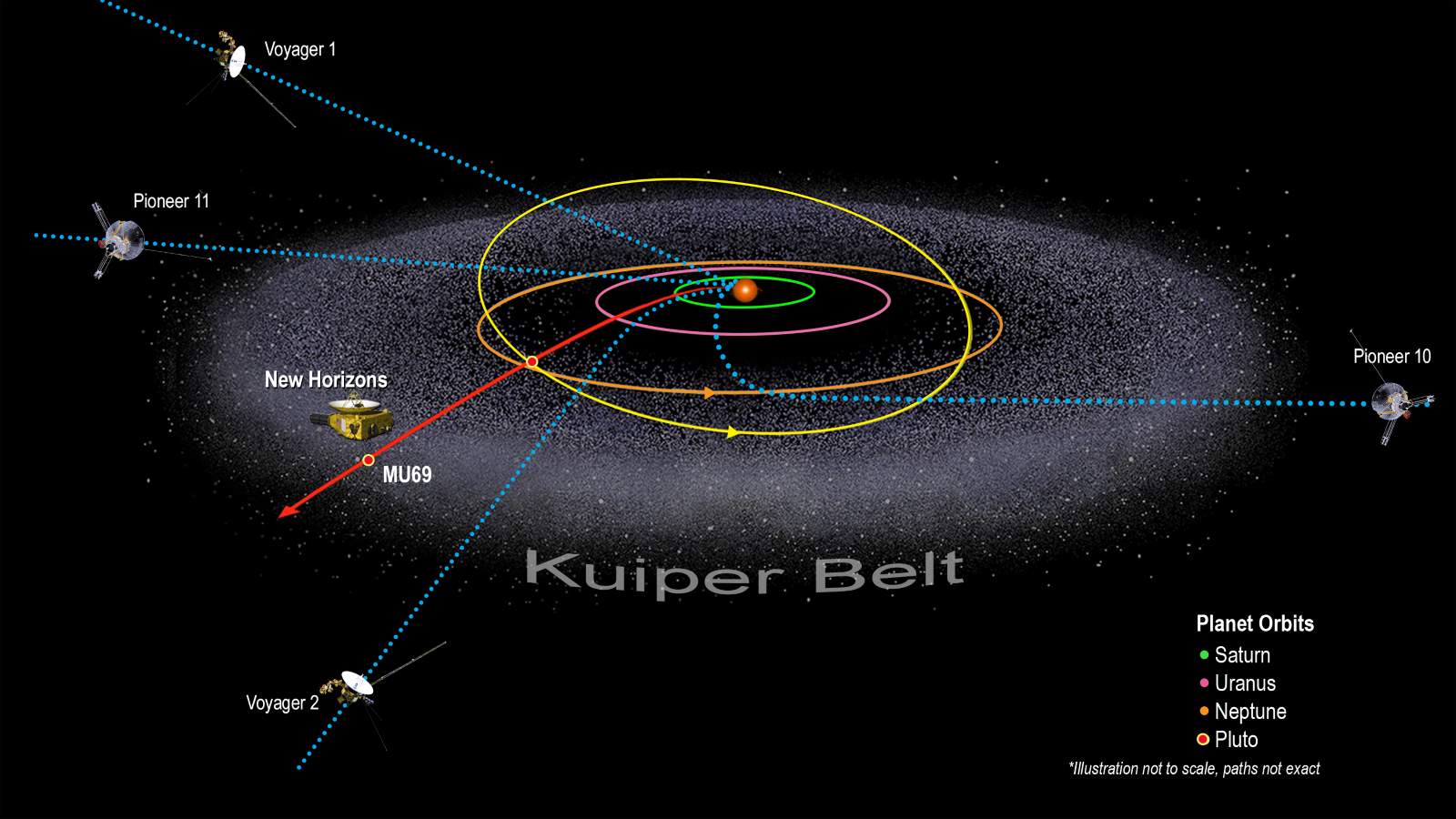

One thing the bogus data hasn’t done is trigger any of the “safe mode” operating systems for the probe, which could have shut down much of its functionality. Other than the wonky data, Voyager 1 is operating normally and continues to send valuable scientific data from 14.5 billion miles away. It and its sister craft, Voyager 2, are our only probes to have currently gone outside of the solar system and are able to collect data where no one has gone before.

Voyager 2 seems to be acting fine as well, returning normal telemetry and other data from 12.1 billion miles away. That points to something specifically going wrong with Voyager 1’s systems. Potential solutions include software changes or switching to a redundant hardware system typically used for backup.

This wouldn’t be the first time Voyager’s engineers would bring up a backup system. In 2017, the probe’s main thrusters began to fail, so the flight engineers switched to thrusters that were initially used to maneuver the probe around planets back in the 70s. They worked like a charm, even though they hadn’t been used in 37 years.

There is a longer-term problem, though – every year, the reactor that has been powering Voyager all this time produces four fewer watts per year. Over time this has caused the mission team to turn off some of the craft’s subsystems in an effort to direct the power where it is needed most.

Eventually, all of them will have to be powered off. Still, until that time, which seems to be later than 2025 at least, the mission team will keep getting as much invaluable data as possible from the most distant ambassador of our species.

Video: Where are the Voyagers Now?

Video: Where will the Voyagers go next?

NASA says “Engineers Investigating NASA’s Voyager 1 Telemetry Data”

Here is the NASA’s press release about the technical difficulty of Voyager 1 below:

The engineering team with NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft is trying to solve a mystery: The interstellar explorer is operating normally, receiving and executing commands from Earth, along with gathering and returning science data. But readouts from the probe’s attitude articulation and control system (AACS) don’t reflect what’s actually happening onboard.

The AACS controls the 45-year-old spacecraft’s orientation. Among other tasks, it keeps Voyager 1’s high-gain antenna pointed precisely at Earth, enabling it to send data home. All signs suggest the AACS is still working, but the telemetry data it’s returning is invalid. For instance, the data may appear to be randomly generated or does not reflect any possible state the AACS could be in.

The issue hasn’t triggered any onboard fault protection systems, which are designed to put the spacecraft into “safe mode” – a state where only essential operations are carried out, giving engineers time to diagnose an issue. Voyager 1’s signal hasn’t weakened, either, which suggests the high-gain antenna remains in its prescribed orientation with Earth.

The team will continue to monitor the signal closely as they continue to determine whether the invalid data is coming directly from the AACS or another system involved in producing and sending telemetry data. Until the nature of the issue is better understood, the team cannot anticipate whether this might affect how long the spacecraft can collect and transmit science data.

Voyager 1 is currently 14.5 billion miles (23.3 billion kilometers) from Earth, and it takes light 20 hours and 33 minutes to travel that difference. That means it takes roughly two days to send a message to Voyager 1 and get a response – a delay the mission team is well accustomed to.

“A mystery like this is sort of par for the course at this stage of the Voyager mission,” said Suzanne Dodd, project manager for Voyager 1 and 2 at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. “The spacecraft are both almost 45 years old, which is far beyond what the mission planners anticipated. We’re also in interstellar space – a high-radiation environment that no spacecraft have flown in before. So there are some big challenges for the engineering team. But I think if there’s a way to solve this issue with the AACS, our team will find it.”

It’s possible the team may not find the source of the anomaly and will instead adapt to it, Dodd said. If they do find the source, they may be able to solve the issue through software changes or potentially by using one of the spacecraft’s redundant hardware systems.

It wouldn’t be the first time the Voyager team has relied on backup hardware: In 2017, Voyager 1’s primary thrusters showed signs of degradation, so engineers switched to another set of thrusters that had originally been used during the spacecraft’s planetary encounters. Those thrusters worked, despite having been unused for 37 years.

Voyager 1’s twin, Voyager 2 (currently 12.1 billion miles, or 19.5 billion kilometers, from Earth), continues to operate normally.

Launched in 1977, both Voyagers have operated far longer than mission planners expected, and are the only spacecraft to collect data in interstellar space. The information they provide from this region has helped drive a deeper understanding of the heliosphere, the diffuse barrier the Sun creates around the planets in our solar system.

Each spacecraft produces about 4 fewer watts of electrical power a year, limiting the number of systems the craft can run. The mission engineering team has switched off various subsystems and heaters in order to reserve power for science instruments and critical systems. No science instruments have been turned off yet as a result of the diminishing power, and the Voyager team is working to keep the two spacecraft operating and returning unique science beyond 2025.

While the engineers continue to work at solving the mystery that Voyager 1 has presented them, the mission’s scientists will continue to make the most of the data coming down from the spacecraft’s unique vantage point.

Sources and Further Reading

- This article was originally published on Universe Today with the title “Voyager 1 Doesn’t Know Where it is, Generating Random-Looking Telemetry Data” by Andy Tomaswick.

- “NASA has Figured Out How to Extend the Lives of the Voyagers Even Longer” on Universe Today

- Voyager 1 on Wikipedia