On August 25, 1989, Voyager 2 performed a close Neptune flyby, giving humanity its first close-up of the eighth (and the outermost) planet of our solar system. Neptune was the spacecraft’s final planetary target.

That first Neptune flyby was also the last: No other spacecraft has visited Neptune since.

Today’s (August 25) story of what happened this day in Science, Technology, Astronomy, and Space Exploration history.

Voyager 2’s historic Neptune flyby

12 years after leaving Earth in 1977, Voyager 2 performed its historic Neptune flyby. It also made its closest approach to any planet by passing about 4,950 kilometers (3,000 miles) above Neptune’s north pole.

Five hours later this closest approach, Voyager 2 passed about 40,000 kilometers (25,000 miles) from Neptune’s largest moon, Triton, the last solid body the spacecraft will have an opportunity to study.

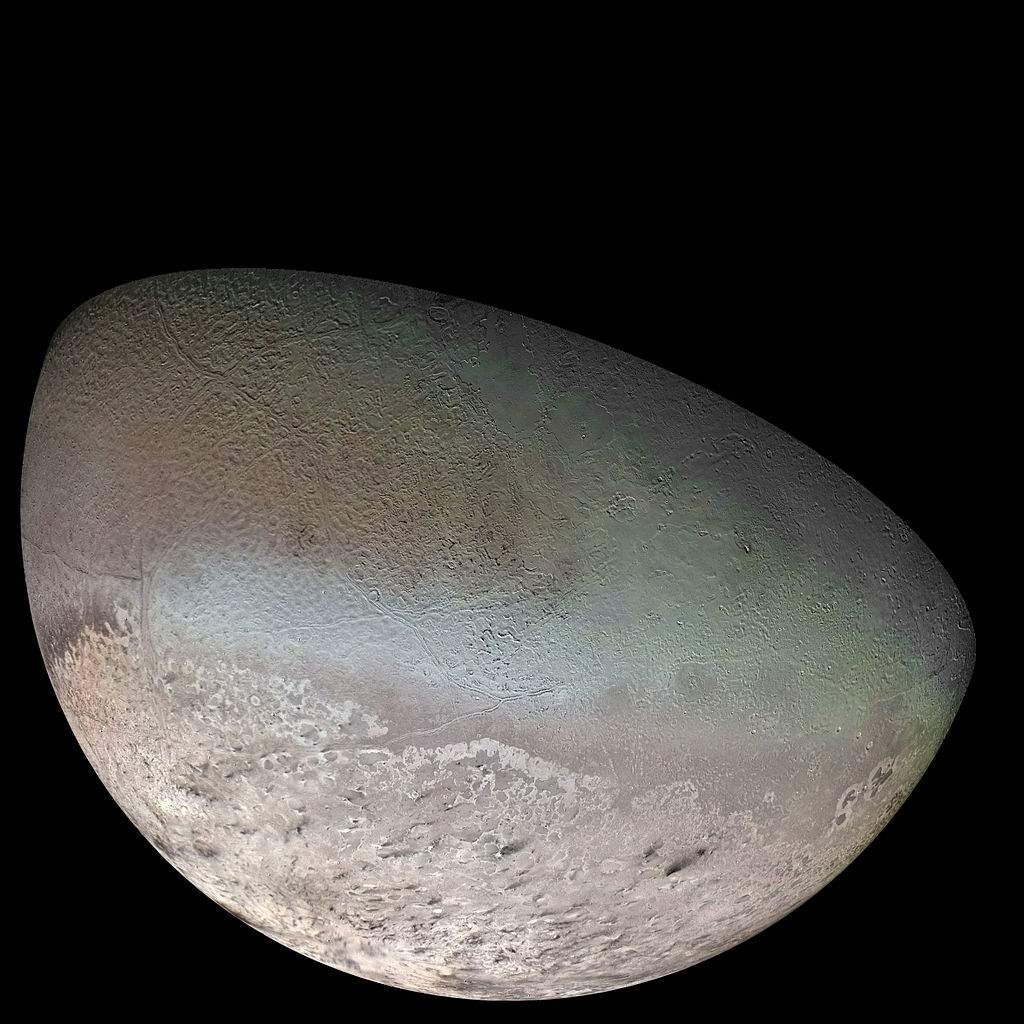

The photo below is a global color mosaic of Triton, taken in 1989 by Voyager 2 during its flyby of the Neptune system. The color was synthesized by combining high-resolution images taken through orange, violet, and ultraviolet filters; these images were displayed as red, green, and blue images and combined to create this color version.

With a radius of 1,350 km (839 mi), about 22% smaller than Earth’s moon, Triton is by far the largest satellite of Neptune. It is one of only three objects in the Solar System known to have a nitrogen-dominated atmosphere (the others are Earth and Saturn’s giant moon, Titan).

Triton has the coldest surface known anywhere in the Solar System (38 K, about -391 degrees Fahrenheit); it is so cold that most of Triton’s nitrogen is condensed as frost, making it the only satellite in the Solar System known to have a surface made mainly of nitrogen ice. The pinkish deposits constitute a vast south polar cap believed to contain methane ice, which would have reacted under sunlight to form pink or red compounds.

The dark streaks overlying these pink ices are believed to be an icy and perhaps carbonaceous dust deposited from huge geyser-like plumes, some of which were found to be active during the Voyager 2 flyby.

The bluish-green band visible in this image extends all the way around Triton near the equator; it may consist of relatively fresh nitrogen frost deposits. The greenish areas include what is called the cantaloupe terrain, whose origin is unknown, and a set of “cryovolcanic” landscapes apparently produced by icy-cold liquids (now frozen) erupted from Triton’s interior.

Video: Voyager 2 Reaches Neptune (CBS Evening News, August 18, 1989)

A delightful piece of history.

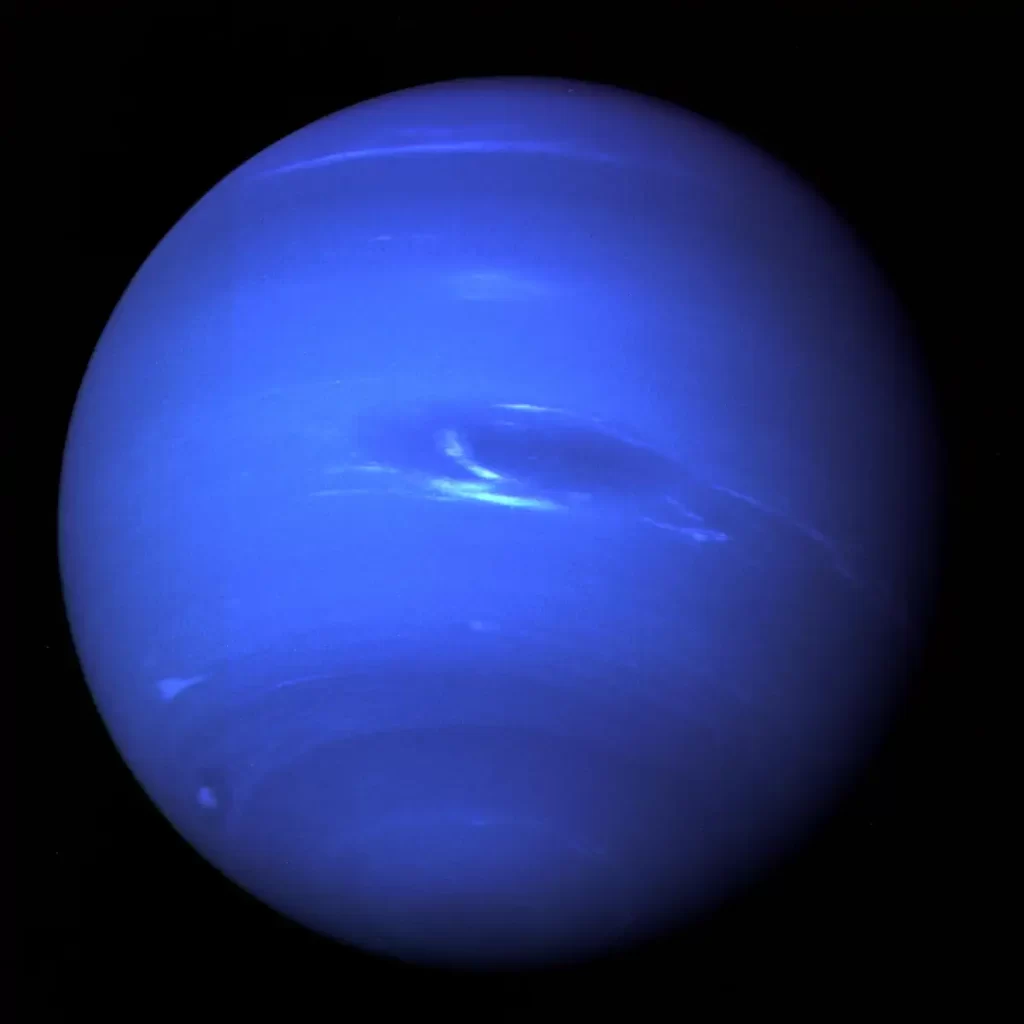

Neptune

Neptune is one of our solar system’s four gas giants. The others in this class are Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus. All four gas giants are beyond the asteroid belt.

These gas giants are about 4 (Neptune) to 12 times (Jupiter) greater in diameter than Earth. They have no solid surfaces but possess massive atmospheres that contain substantial amounts of hydrogen and helium with traces of other gases.

Neptune is the fourth-largest planet by diameter (after Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus), the third-most-massive planet (after Jupiter and Saturn), and the densest giant planet. It is 17 times the mass of Earth, and slightly more massive than its near-twin Uranus.

Neptune completes an orbit around Sun in 164.8 years (60,195 days). Its equatorial radius of 24,764 km (15,388 miles) is nearly four times that of Earth.

Neptune has a faint and fragmented ring system (labeled “arcs”), which was discovered in 1984. This ring system was then later confirmed during Voyager 2’s Neptune flyby.

About 30 times farther from the Sun than Earth is, the icy giant receives only about 0.001 times the amount of sunlight that Earth does. In such low light, Voyager 2’s camera required longer exposures to get quality images. However, because the spacecraft would reach a maximum speed of about 60,000 mph (90,000 kph) relative to Earth, a long exposure time would make the image blurry. (Imagine trying to take a picture of a roadside sign from the window of a speeding car.)

So the team programmed Voyager 2’s thrusters to fire gently during the close approach, rotating the spacecraft to keep the camera focused on its target without interrupting the spacecraft’s overall speed and direction.

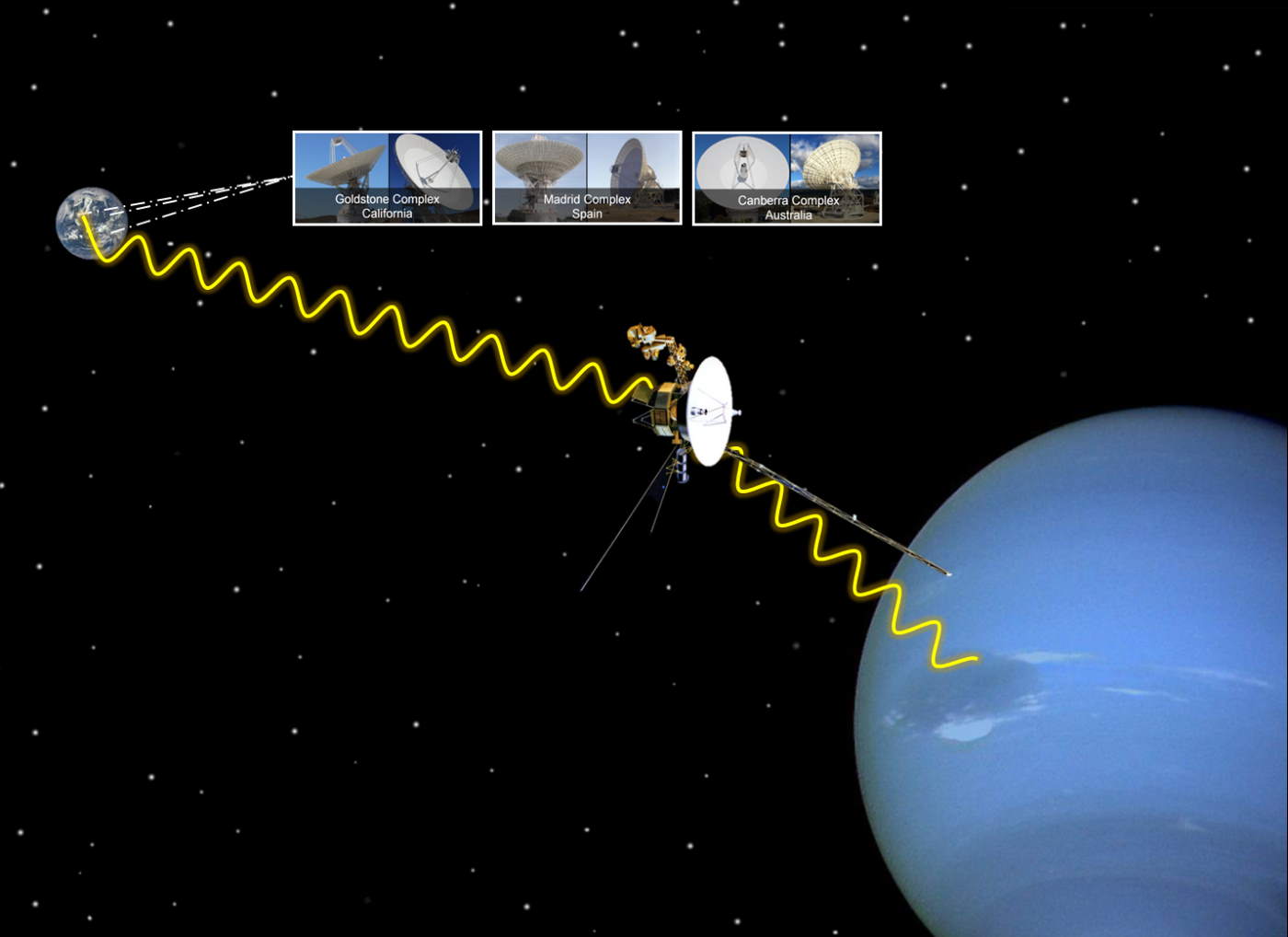

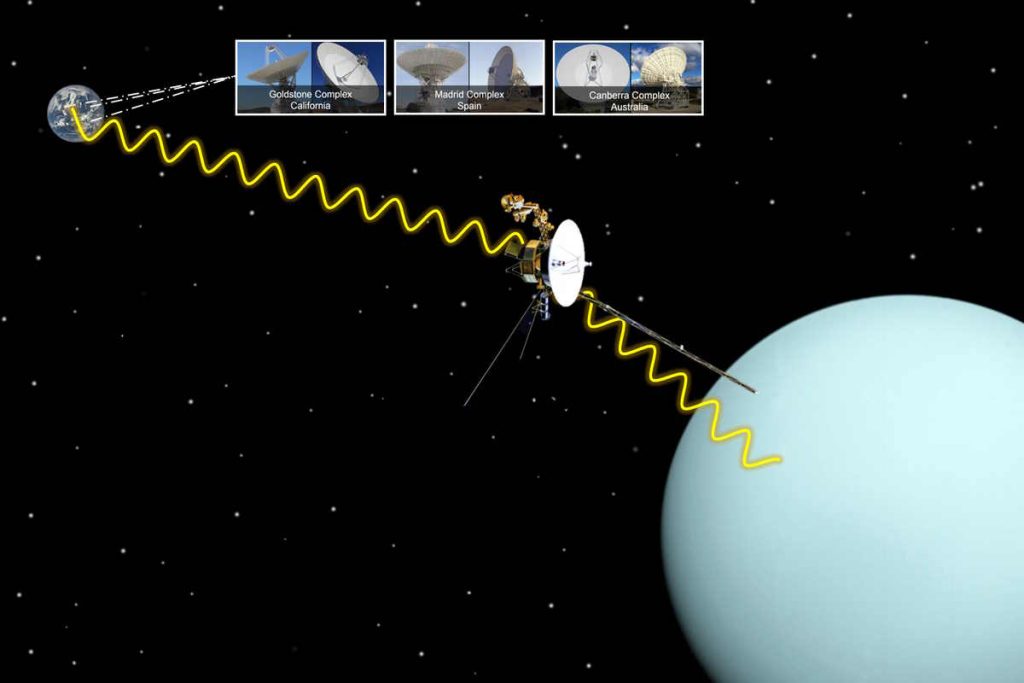

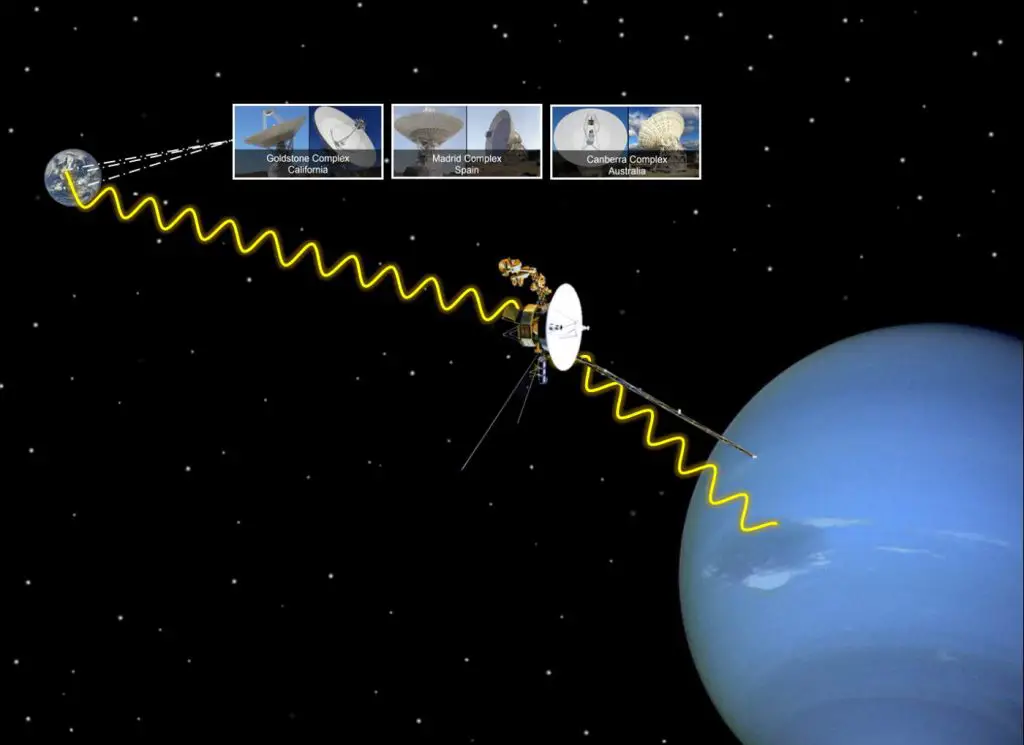

The probe’s great distance also meant that by the time radio signals from Voyager 2 reached Earth, they were weaker than those of other flybys. But the spacecraft had the advantage of time: The Voyagers communicate with Earth via the Deep Space Network, or DSN, which utilizes radio antennas at sites in Madrid, Spain; Canberra, Australia; and Goldstone, California.

During Voyager 2’s Uranus encounter in 1986, the three largest DSN antennas were 64 meters (210 feet) wide.

To assist with the Neptune encounter, the DSN expanded the dishes to 70 meters (230 feet). They also included nearby non-DSN antennas to collect data, including another 64-meter (210 feet) dish in Parkes, Australia, and multiple 25-meter (82 feet) antennas at the Very Large Array in New Mexico

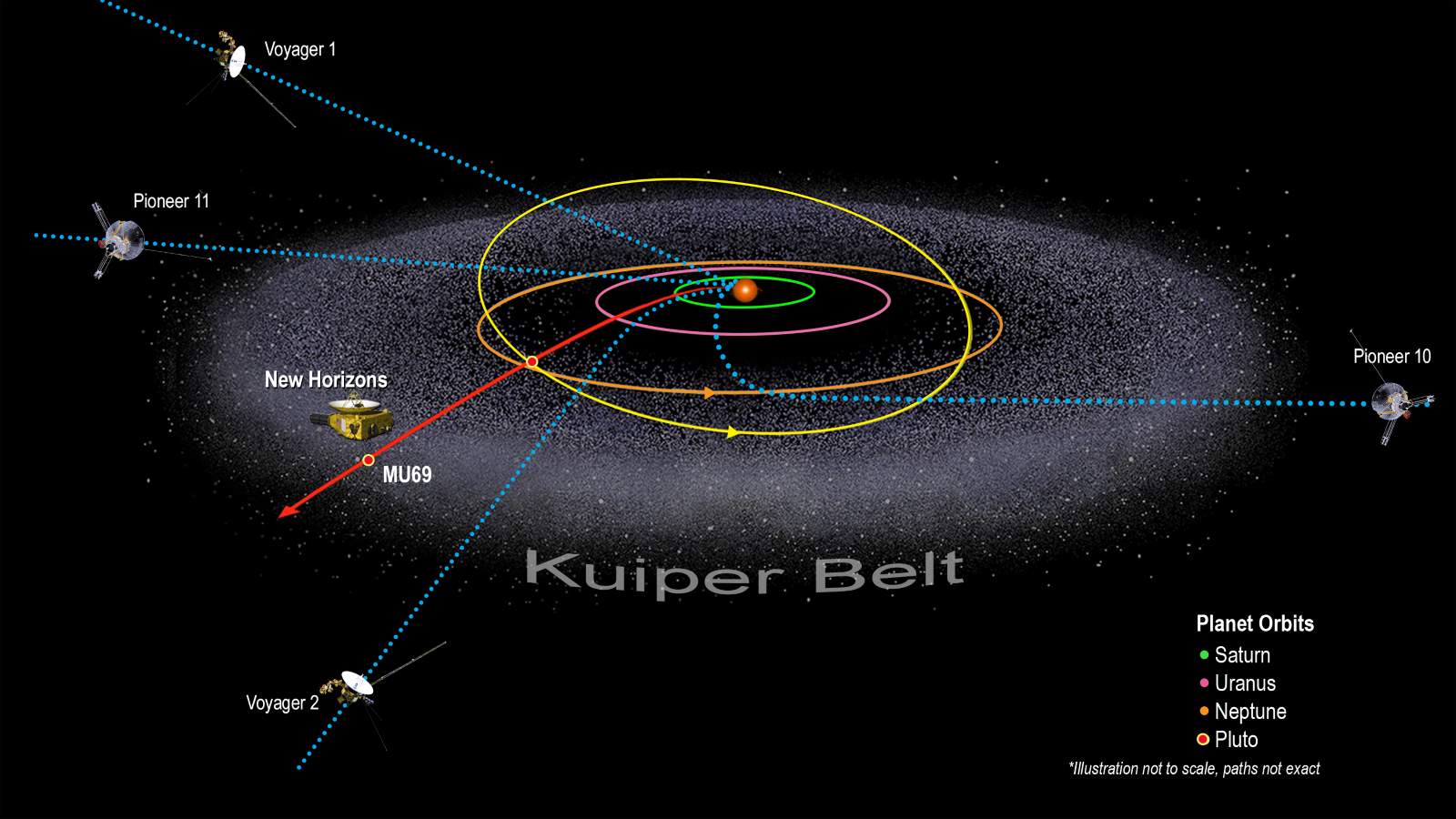

The conclusion of the Neptune flyby marked the beginning of the Voyager Interstellar Mission, which continues today, 45 years after launch (as of 2022). Voyager 2 and its twin, Voyager 1 (which had also flown by Jupiter and Saturn), continue to send back dispatches from the outer reaches of our solar system.

August 20 in Science, Technology, Astronomy, and Space Exploration history

- 2012: Voyager 1 passed the heliopause and became the first spacecraft in interstellar space

- 1989: Voyager 2 performed the first Neptune flyby

Sources

- “Voyager 2 and Neptune” on the NASA website

- “Voyager 2’s Historic Neptune Flyby” on the NASA website

- “Neptune Approach” on the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory website

- Moon Landings: All-Time List [1966-2025] - February 2, 2025

- What Is Max-Q and Why Is It Important During Rocket Launches? - January 16, 2025

- Top 10 Tallest Rockets Ever Launched [2025 Update] - January 16, 2025