The question of where the evolutionary cradle of modern humans lies has long intrigued scientists and historians. The East African Great Rift Valley has traditionally been viewed as the most likely birthplace. However, revolutionary research conducted recently presents a compelling alternative.

This groundbreaking study utilizes DNA evidence to trace back the origins of mankind to a prehistoric wetland known as Makgadikgadi-Okavango, located south of the Great Zambezi River. This finding significantly shifts the focus of anthropological inquiry from East Africa to Southern Africa.

In a landmark study published in the prestigious journal Nature, it was revealed that the earliest population of H. sapiens sapiens, our direct ancestors, emerged approximately 200,000 years ago in an area that encompasses parts of what is now modern-day Botswana, Namibia, and Zimbabwe.

The research unraveled a hitherto unappreciated chapter of human history, infusing fresh life into the story of human evolution. This revelation underscores the intricate tapestry of the human lineage and affirms the complexities underlying our understanding of human evolution.

Botswana: the starting point of humanity’s journey

Today, the region is characterized by its dry and dusty terrain, speckled with scattered salt pans, a stark contrast to the vibrant wetlands that once dominated the landscape. It’s quite challenging to imagine that this was the place where modern humans not only lived, but thrived for an impressive span of 70,000 years, before our ancestors embarked on the journey that led them to explore the rest of Africa, and eventually the entire world.

Scientists were able to pinpoint this specific region through a meticulous study of mitochondrial DNA, commonly referred to as the ‘mitogenome.’ Unlike nuclear DNA, which is inherited from both parents, mitochondrial DNA is exclusively passed on from the mother. This unique characteristic means that it isn’t mixed up in each new generation.

When envisioning all modern humans as occupying a specific spot on a vast family tree, it’s logical to anticipate the most diverse mitogenome to be found in the area where humans first evolved. Thus, the extraordinary variety in the mitochondrial DNA in this region underlines its vital role in human history and evolution.

Related: Okavango Delta, Botswana

The “mitogenome” refers to the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), a small circular genome located within a cell’s mitochondria. Unlike nuclear DNA, which is inherited from both parents and recombined in each generation, mitochondrial DNA is passed down exclusively from the mother, maintaining a relatively unchanged lineage.

This mtDNA encodes essential information for the function of the mitochondria, often termed the “powerhouses of the cell,” responsible for producing most of the energy needed for cellular function. Scientists often study the mitogenome to trace maternal lineage and to understand human evolution and migration patterns because of its unique inheritance pattern and rapid mutation rate. It offers a rich source of genetic data, assisting in piecing together the vast and complex puzzle of human history.

Scientists are already aware that genetic data points to southern Africa as humanity’s birthplace, a location contrasted by fossil evidence that has been predominantly found in East Africa. However, they sought to refine this understanding, aiming to pinpoint the precise location where humans first evolved.

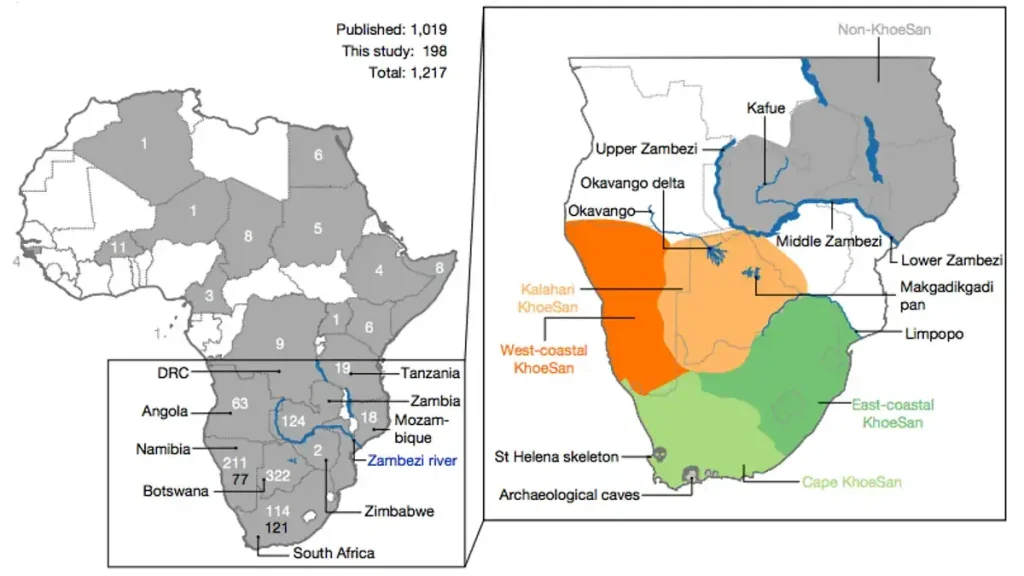

In this pursuit, their focus shifted to the KhoeSan people, a group known to have the most diverse mitogenomes on the planet. This genetic diversity suggests that their DNA mirrors most closely that of our shared ancestral origins. Considering the human family tree, if everyone is situated on its branches, the KhoeSan represents the trunk of this tree.

The KhoeSan are recognized for their unique linguistic feature of click sounds in their languages and culturally as foragers. Some San communities continue to uphold these ancestral ways of life, engaging in hunting and gathering for sustenance.

Over the past decade, members of the research team have engaged in extensive work with KhoeSan communities, as well as with other ethnicities and language groups, within Namibia and South Africa, contributing significantly to this monumental discovery.

By generating mitogenome data for around 200 rare or newly discovered sub-branches of KhoeSan lineages, and merging them with all available data, we were able to zoom in on the very base of our evolutionary tree.

It is now clear our ancestors must have dispersed from a region south of the Zambezi River. This is consistent with geographical, archaeological, and climate data, including the fact that this area would have been a fertile wetland at the time the first modern humans emerged.

By generating mitogenome data for approximately 200 rare or newly identified sub-branches of KhoeSan lineages and integrating them with all accessible data, scientists have managed to zoom in on the very foundation of our evolutionary tree.

The evidence now unequivocally indicates that our ancestors must have originated from a region located south of the Zambezi River. This conclusion is harmonious with existing geographical, archaeological, and climate data. It also aligns with the understanding that this area would have been a lush, fertile wetland during the time when the first modern humans began to emerge. This blend of scientific disciplines and data points firmly establishes this region as the cradle of modern humanity.

Why humanity left its birthplace, Botswana, and spread across the world?

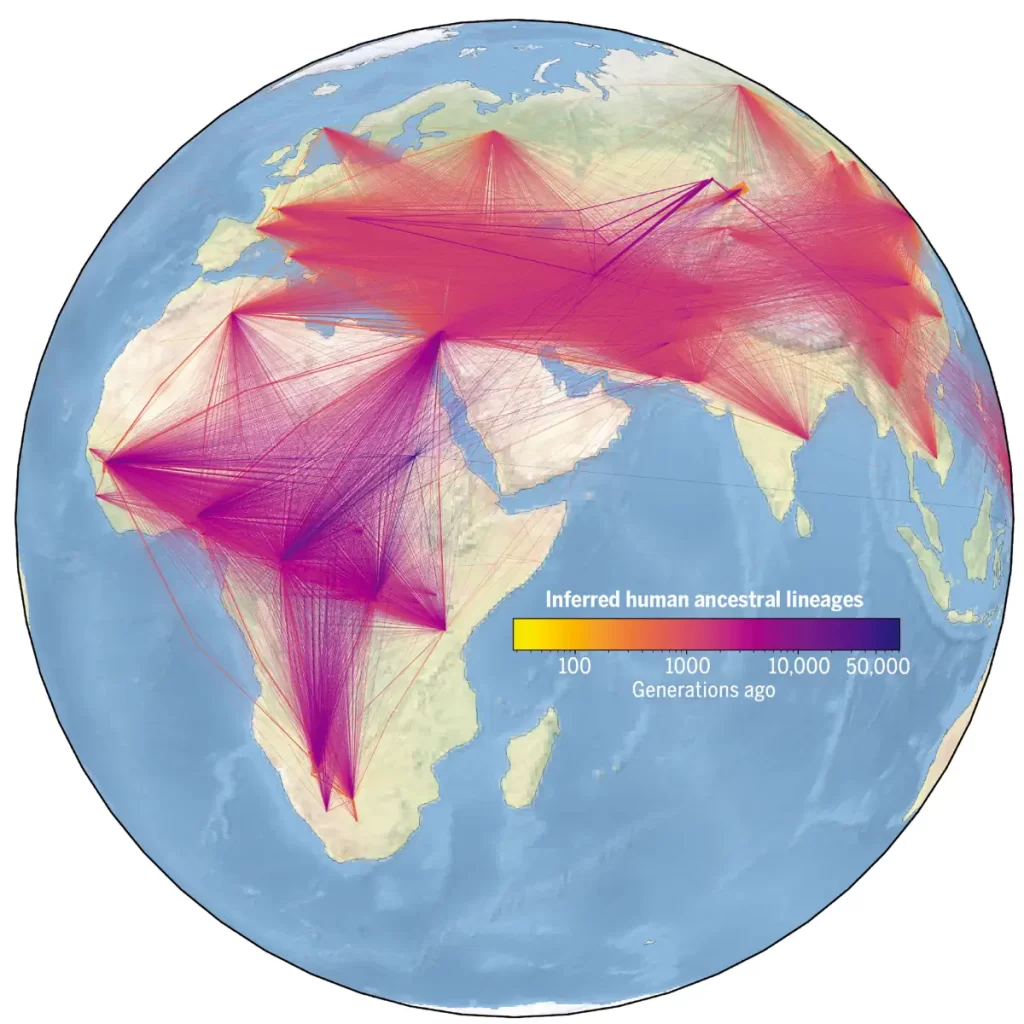

Humans spread across the world through a process known as migration. Originating from Africa, the earliest humans began to move across continents over thousands of years. This was often driven by the need to find new food sources and suitable habitats as climates and landscapes changed. They traversed vast land masses and bodies of water, establishing settlements, and over time, adapting to various environments. Their adaptability led to the emergence of distinct populations or groups with unique cultures and physical characteristics based on their geographical location.

But why? Why humans left the “heaven” and embarked on a challenging journey?

Scientists have found compelling geological evidence pointing towards the fact that millions of years ago, a significant shift in the terrain led to the fragmentation of the prehistoric Makgadikgadi Lake that once dominated the region. This monumental shift would have consequently given rise to a vast expanse of wetlands, fostering the conditions conducive to sustaining life.

One might question, if the area was so perfectly suited to support life, why did the ancestors of modern humans begin to venture out of their birthplace between 130,000 and 110,000 years ago? These explorations initially veered towards the northeast before eventually heading southwest away from their original home.

Climate data has offered some clarity, suggesting that around that time, the region fell prey to a severe drought. Around 130,000 years ago, there was a marked increase in humidity in the northeast part of the homeland, and similar changes occurred in the southwest 20,000 years later. Scientists surmise that this shift led to the development of lush vegetation corridors, which our ancestors would have followed as they ventured into new territories, likely trailing after the migration of game animals.

Interestingly, genetic evidence indicates that those who ventured south populated the entire southern coast of Africa, creating a network of thriving sub-populations. Archaeological findings in the Blombos caves in South Africa lend weight to this hypothesis, showcasing evidence of advanced human cognitive behavior dating back to approximately 100,000 years ago.

Scientists were amazed by the remarkable coherence between timeline data spanning across distinct yet interconnected disciplines that had historically operated in isolation. This unprecedented integration allowed scientists to hypothesize that the success of the southern migrants was likely due to their adaptation to harnessing the rich marine resources.

Even as the earliest explorers ventured out, a portion of the population remained behind, continuing to inhabit the ancestral homeland. They have evolved and adapted to the now much drier landscape. Scientists have spent the last decade interacting with the last descendants of humanity’s homeland, such as the Ju/’hoansi people of the Kalahari in Namibia.

The Ju/’hoansi, who still practice their traditional way of life, have warmly received the scientists’ findings. They believe the study validates a history that they have preserved and shared across generations through oral storytelling. The tale that is told, it is now clear, is not merely their story but a shared narrative of all humankind.

- Space Shuttle Endeavour’s Touchdown Meets Columbia’s Salute [An amazing photo from the past] - February 29, 2024

- Moon Landings: All-Time List [1966-2024] - February 23, 2024

- From Orbit to Ordinary: 10 Earthly Applications of Space Technology - January 23, 2024