On October 4, 1957, the first artificial satellite Sputnik 1, was launched by the Soviet Union. Thus, began the space age. It orbited the Earth until January 4, 1958. Sputnik 1 made 1440 orbits and traveled about 70 million kilometers (43 million miles).

The successful launch shocked the world, according to NASA, and gave the former Soviet Union the distinction of putting the first human-made object into space. Its “unanticipated” success precipitated the Sputnik crisis in the United States and triggered the Space Race, a part of the Cold War.

Today’s (October 4) story of what happened this day in Science, Technology, Astronomy, and Space Exploration history.

Sputnik 1

Sputnik 1 was launched on October 4, 1957, from Baikonur Cosmodrome at Tyuratam (370 km / 23m mi southwest of the small town of Baikonur) in Kazakhstan, then part of the former Soviet Union.

The word “Sputnik” originally meant “fellow traveler,” but has become synonymous with “satellite” in modern Russian.

Sputnik 1 was the first in a series of four satellites as part of the Sputnik program of the former Soviet Union and was planned as a contribution to the International Geophysical Year (an international scientific project that lasted from July 1, 1957, to December 31, 1958, see notes 1).

Three of these satellites (Sputnik 1, 2, and 3) reached Earth orbit.

Sputnik 1 size and properties

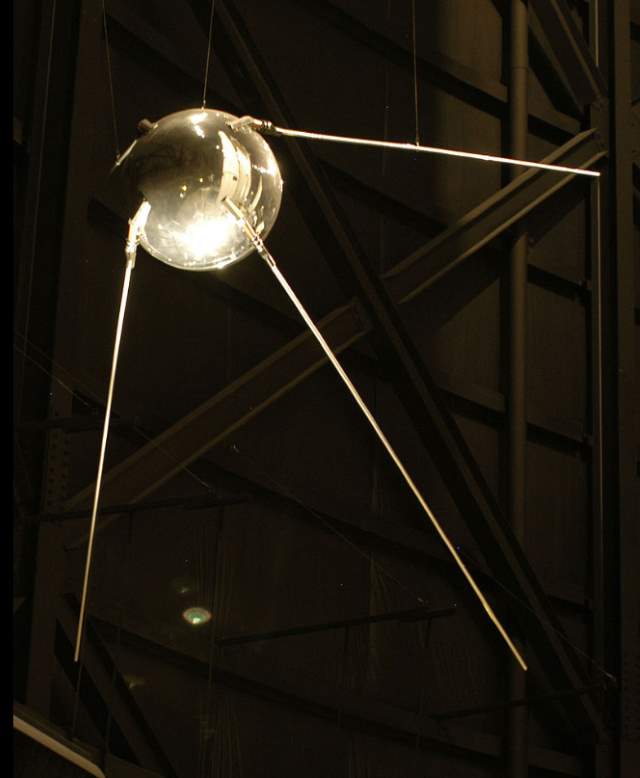

Sputnik 1 was a 58 cm-diameter (22.8 inches) aluminum sphere that carried four whip-like antennas that were 2.4-2.9 meters (7.87-9.5 feet) long. The antennas looked like long “whiskers” pointing to one side.

The spacecraft obtained data pertaining to the density of the upper layers of the atmosphere and the propagation of radio signals in the ionosphere. The instruments and electric power sources were housed in a sealed capsule and included transmitters operated at 20.005 and 40.002 MHz (about 15 and 7.5 m in wavelength), the emissions taking place in alternating groups of 0.3 s in duration.

The downlink telemetry included data on temperatures inside and on the surface of the sphere.

The speed of Sputnik 1

Sputnik 1 traveled at about 29,000 km/h (18,000 mph; 8,100 m/s), taking 96.2 minutes to complete each orbit.

It transmitted on 20.005 and 40.002 MHz, which were monitored by radio operators throughout the world. The signals continued for 21 days until the transmitter batteries ran out on 26 October 1957.

Sputnik burned up on 4 January 1958 while reentering Earth’s atmosphere, after three months, 1440 completed orbits of the Earth, and a distance traveled of about 70 million km (43 million mi).

Sputnik 1 Booster also reached Earth orbit

The Sputnik 1 rocket booster also reached Earth orbit and was visible from the ground at night as a first magnitude object, while the small but highly polished sphere, barely visible at sixth magnitude, was more difficult to follow optically.

Sputnik 1 was not visible to the naked eye

There was a common misconception that Sputnik 1 was visible to the naked eye, and easily be seen through binoculars: no, it was not. In fact, what people were seeing was the second stage of the R-7 rocket which was in the same orbit as Sputnik 1.

Sputnik 1 itself was way too small to be seen from Earth, neither with the naked eye nor through binoculars.

It even had already flown over the United States twice, undetected, before the Soviet news agency TASS confirmed its existence to the world.

Sputnik 1 replicas

Several replicas of the Sputnik 1 satellite can be seen at museums in Russia and another is on display in the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

Video: Sputnik 1 – the Start of the Space Race

Modern satellites and GPS

The launch of Sputnik also planted the seeds for the development of modern satellite navigation. Two American physicists, William Guier, and George Weiffenbach, at Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), decided to monitor Sputnik’s radio transmissions and within hours realized that, because of the Doppler effect, they could pinpoint where the satellite was along its orbit.

The Director of the APL gave them access to their UNIVAC I (see notes 2) to do the heavy calculations required.

Early the next year, Frank McClure, the deputy director of the APL, asked Guier and Weiffenbach to investigate the inverse problem: pinpointing the user’s location, given the satellite’s. At the time, the Navy was developing the submarine-launched Polaris missile, which required them to know the submarine’s location. This led them and APL to develop the TRANSIT system, a forerunner of modern Global Positioning System (GPS) satellites.

Notes

- The International Geophysical Year was an international scientific project that lasted from 1 July 1957 to 31 December 1958. It marked the end of a long period during the Cold War when scientific interchange between East and West had been seriously interrupted. 67 countries (including the United States and the Soviet Union) participated in IGY projects, although one notable exception was the mainland People’s Republic of China, which was protesting against the participation of the Republic of China (Taiwan).

- The UNIVAC I (UNIVersal Automatic Computer I) was the first general-purpose electronic digital computer design for business applications produced in the United States. UNIVAC I used about 5,000 vacuum tubes, weighed 16,686 pounds (8.3 short tons; 7.6 t), consumed 125 kW, and could perform about 1,905 operations per second running on a 2.25 MHz clock. The Central Complex alone (i.e. the processor and memory unit) was 4.3 meters (14.1 feet) by 2.4 meters (7.87 feet) by 2.6 meters (8.53 feet) high. The complete system occupied more than 35.5 m² (382 ft²) of floor space.

Sources

- Sputnik 1 on Wikipedia

- Sputnik 1 on NASA.gov

- UNIVAC I on Wikipedia

- Sputnik 1 on the NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive website

- Moon Landings: All-Time List [1966-2025] - February 2, 2025

- What Is Max-Q and Why Is It Important During Rocket Launches? - January 16, 2025

- Top 10 Tallest Rockets Ever Launched [2025 Update] - January 16, 2025