The American Veterans Center published a video, a conversation with the Apollo 17 moonwalker Harrison Schmitt. Schmitt was the first geologist to visit the lunar surface. He talks about the mission, and especially, the importance of the moon rocks.

A Conversation with the Apollo 17 Moonwalker Harrison Schmitt [transcript of the video]

The one thing you can’t simulate during launch simulations is the vibration that the rocket has when it’s starting off. The first stage of the Saturn V rocket developed 7.5 million pounds of thrust with its five big engines. The interaction of the plumes of those engines creates a very heavy, low-frequency vibration in the Saturn V. That’s just something never simulated.

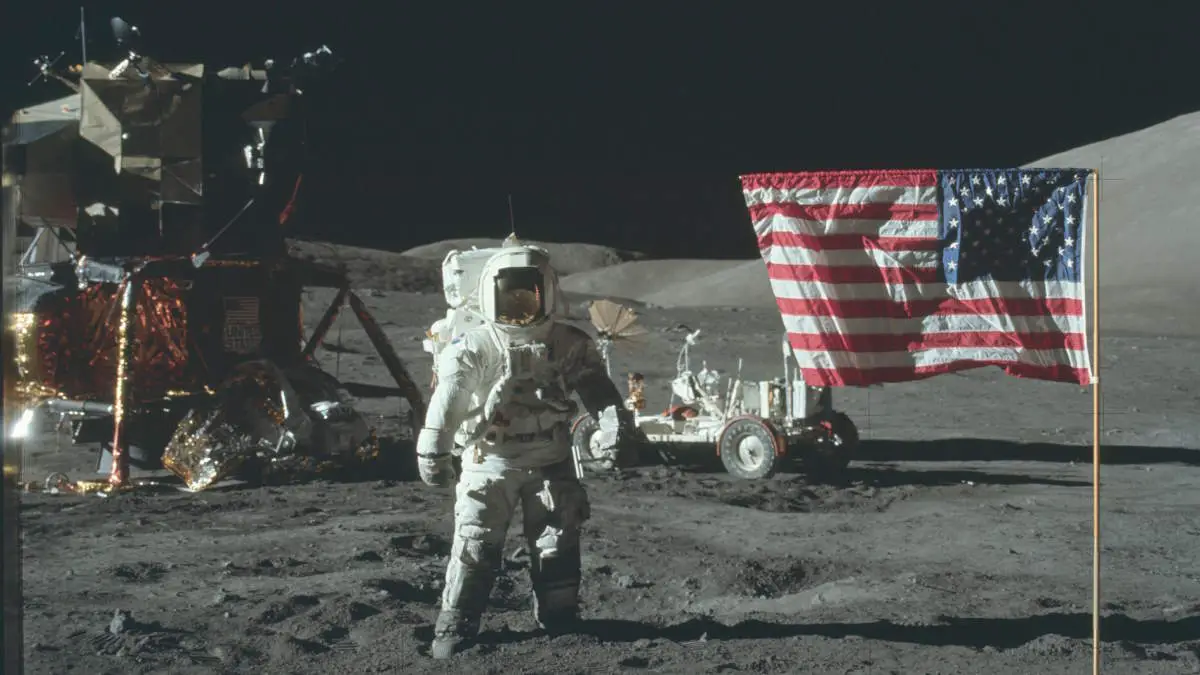

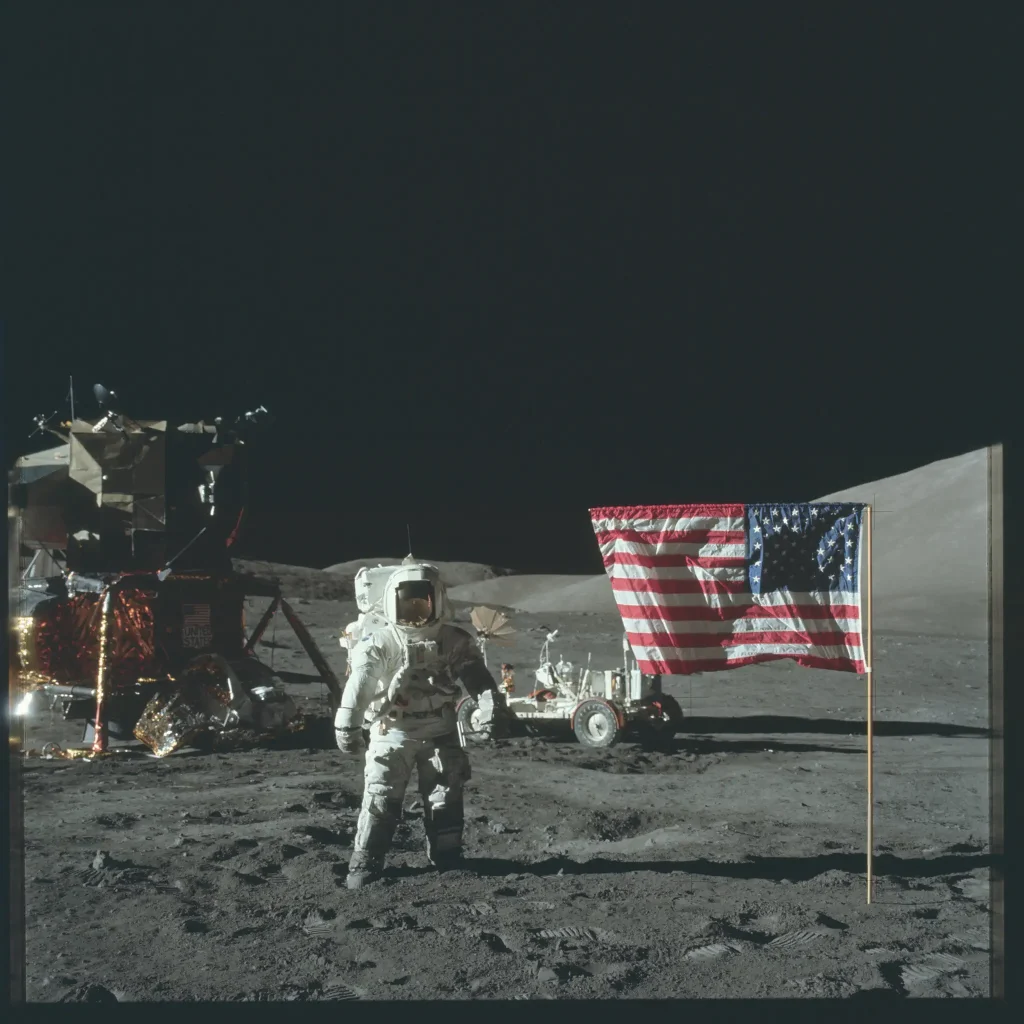

For about the first hour, I was doing things very close to the Lunar Module (LM), to the Challenger [Author’s note: Apollo 17’s Lunar Module was named Challenger]. Getting equipment out of the bays, and things like that. So, it was not that much different, really, visually, than being here back on Earth, dealing with your spacecraft, in the tests and everything. You were looking at the same kind of equipment. Identical equipment. [Author’s note: Schmitt is talking about simulations here.]

[On the Moon] And I didn’t get a chance to take a good look at where I was until the procedures we had developed had me go away from the Lunar Module, maybe about 50 meters or so, and start to take some panoramas before we really stirred up all the soil around the Lunar Module and everything.

So, when I was taking those panoramas, of course, I was clicking on a camera that was mounted on my chest, but I was also looking at… that was the first chance I had to see this magnificent valley, as I said, deeper than the Grand Canyon, brilliantly illuminated by the Sun, more brilliantly even than the desert sun that I was used to out in New Mexico. And also, placed against a blacker-than-black sky.

That, I think, was the hardest thing to get used to. Because, here on Earth, when you have a brilliant sun, you have a blue sky. Well, the sky around the Moon was black.

The Blue Marble photo

[Schmitt tells the story of the famous Blue Marble photo, one of the most iconic photos of Earth taken from space.]

Blue Marble photo was taken on the way to the Moon, and soon after the launch, as a matter of fact, because, we were close enough to the Earth. In order to see the entire sphere, it was basically a Full Earth. The Blue Marble photograph, I took as part of a long series of photographs that document my weather observations of the Earth.

That was one of the major activities I had planned to do. That wasn’t in the flight plan, but I planned to do as an amateur meteorologist to look at the weather patterns of the Southern Hemisphere and how they, not only what they were, but how they developed over the course of three days [Author’s note: it took 3 days to reach Moon during Apollo missions].

[Interviewer asks:]

– What it’s like to know that you took one of the most famous pictures [of Earth from space] ever?

Well, I didn’t realize that until many weeks after the mission, because it was part of the series of photographs that document weather observations. But, it really, was very gratifying that people enjoyed that picture.

NASA tells me that “It’s the most requested photograph from the Apollo archives”. I am really very proud of it.

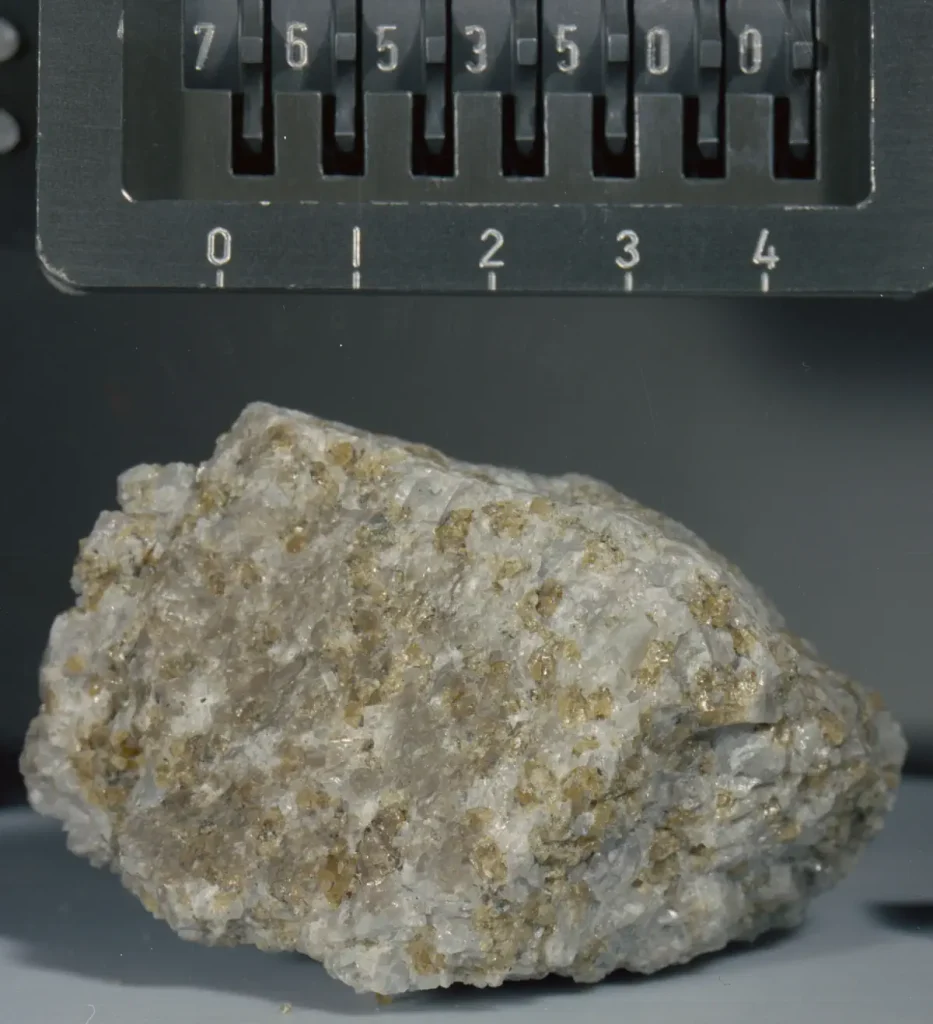

Troctolite 76535

[Author’s note: Troctolite 76535 is a notable lunar sample, classified as a troctolite, a type of igneous rock. It was collected from the Moon’s surface by astronauts during the Apollo 17 mission in 1972. This sample is significant due to its unique composition, which is distinct from typical lunar basalts. It contains a high proportion of olivine and plagioclase, providing valuable insights into the Moon’s geological history and the processes that shaped its crust. Troctolite 76535 remains an important subject of study in lunar science.]

76535 is a rock made up mostly of olivine and a type of pyroxene called orthopyroxene. It is one of two rocks actually that the evidence now, I believe, says, came from deep within the moon. That rock is probably from around 400 kilometers (250 miles) down from the surface. Another rock, 72415, which is almost entirely all olivine, that rock came from a deeper point in the moon, probably around 500 kilometers (310 miles) down.

Those two rocks are the only ones in the collection that people have recognized so far, they have probably come from deep within the moon as a result of a very large impact that occurred about 4.3 billion years ago, called Procolumn.

[Interviewer asks:]

– How do you calculate how far deep it came from?

Mainly by the assemblages of minerals that are in the rock, and the alteration of those minerals due to a pressure change. You see, interestingly enough, I worked on the same kind of problem in Norway for my doctorate thesis.

Where rocks have been formed at very high pressure deep within the Earth, and then very rapidly brought close to the surface by the tectonic dynamics here on Earth… Well, in the case of the Moon, they were brought up by the impact dynamics, by the release of pressure. And when rocks form at high pressure, and then are exposed to low pressure, they change. They give evidence of how the minerals react, and that’s how we can tell how deep they were originally. Because, you see, they partially changed as a result of the pressure release.

[Interviewer asks:]

– I’ve also heard that, to your surprise, I believe, you found some red dirt on the Moon.

It was a surprise, but, on the other hand, it helps to illustrate what field geologists do. You always go into the field with as much understanding as you have about the area that you’re going to study, and you develop what we call multiple hypotheses on how to explain what may be there or what you know is there. Then you try to get new observations to verify one hypothesis versus another.

One of the hypotheses we had for visiting this dark crater called Shorty was that it might be a volcanic crater. So, when I walked up to the edge of that crater and saw this orange color in the debris at the rim of the crater, my first thought was, well, it’s a volcanic crater, because, on Earth, you see colorization around volcanic craters.

This is the first color we have seen in the Valley of Taurus-Littrow, [Author’s note: there is an error in the captions of the video at this point. Taurus-Littrow Valley is the region on the Moon where the Apollo 17 lunar mission landed] so my first thought was, well, maybe it is volcanic.

Well, as soon as I looked at it closely, it was clearly a hundred-meter (330 feet) diameter impact crater, another impact crater. So, how did it get that red color? I am going back and forth trying to figure out how in the world you get volcanic-like color around an impact crater.

Well, we didn’t know at the time that it turned out that this red, orange soil was indeed volcanic ash that had been deposited about 3.5 billion years ago. Then, about 3 million years ago, the crater was formed, Shorty crater was formed and exposed this material.

[Interviewer asks:]

– What is the most significant thing we’ve learned from the lunar materials?

I think the most significant thing that’s been learned is that the Moon and Earth were formed at about the same time, 4.5 billion years ago.

Schmitt: I just feel very grateful that I had a chance to be part of it

[Interviewer asks:]

– Sir, you knew this would be the last mission in the Apollo Program. What was it like getting back onto that Lunar Module for the last time, knowing that you and Gene Cernan were going to be the last ones, at least for a long time, to set foot there?

Well, I wish we could have had the consumables and everything necessary for a fourth EVA [Author’s note: Extravehicular Activity (EVA) refers to any activities astronauts perform outside their spacecraft in space. EVAs are commonly known as spacewalks, but moonwalkings are also EVAs].

Cernan and I talked a little bit in the cabin about where would we go if we had a fourth one, but, the consumables weren’t there primarily because we took payload, we took scientific experiments, several hundred pounds of scientific experiments. Had we not taken those and just had oxygen and water in the spacecraft, we could’ve stayed for another day.

The Lunar Module, Grumman Aircraft Corporation built the Lunar Module really did a fantastic job, and their early predictions were that we would have a Lunar Module that could spend four days on the Moon, and eventually, with modifications, and everything, and growth. That’s what we ended up with.

Three days was an exciting time. I often sit back and think, even with the research that I’m doing now, where would I have gone differently? How would I plan the Apollo 17 mission differently?

[Interviewer asks:]

– If you look back at your service as an astronaut, and as an advisor to other astronauts, what are you most proud of from your time, serving a country in that way?

I think I just have to be proud of having been involved, and being in a position coincidentally, because of my experience and education. To actually be involved in this period of time, was a very, very important period for the United States, for democracy, for the continuation of human freedom, and I just feel very grateful that I had a chance to be part of it.

Harrison Schmitt

Harrison Hagan Schmitt was born July 3, 1935, in Santa Rita, New Mexico. Schmitt currently lives with his family in the Intermountain West.

He received a Bachelor of Science degree in science from the California Institute of Technology in 1957; studied as a Fulbright Fellow at the University of Oslo in Norway from 1957 to 1958; received a doctorate in geology from Harvard University in 1964, based on geological work in western Norway.

In 1957, Schmitt began geological fieldwork on the west coast of Norway, returning there in 1960 to work in that region for the Norwegian Geological Survey.

Schmitt also worked in the field for the United States Geological Survey in New Mexico, Arizona, and Montana. He was with the U.S. Geological Survey’s Astrogeology Branch in Flagstaff, Arizona from 1964-1965, serving as Project Chief for Lunar Field

Geological Methods on contract to NASA.

He also was responsible for a lunar photographic and telescopic mapping project and for instructing NASA astronauts during their early geological training trips.

NASA Experience

Dr. Schmitt was selected in Astronaut Group 4 as a scientist-astronaut in June 1965. As a civilian, Schmitt completed jet and helicopter flight training at Williams Air Force Base, Arizona, and at the Pensacola Naval

Air Station, Florida. He logged more than 2,100 hours of flying time including 1,600 hours in jet aircraft (primarily T-38 Talon) and 210 hours in helicopters (H-13).

During the period of his general preparation for space flight, Schmitt assisted in the integration of operational and scientific activities into the Apollo lunar missions, as well as the planning for lunar orbit and surface operations for Apollo missions 8-13.

These responsibilities included the design and oversight of an upgraded geological training program for Apollo missions 13-17.

Schmitt was designated as the Mission Scientist in support of Apollo 11 and, in early 1970, he was assigned as the Backup Lunar Module Pilot for Apollo 15 that few to the Moon in July 1971.

In August 1971, Schmitt was assigned as Lunar Module Pilot for the Apollo 17 mission. Apollo 17 launched at 12:33 p.m. (EST), on December 7, 1972, and splashed down in the Pacific on December 19, 1972, having completed three days of geological and geophysical exploration in the valley of Taurus-Littrow on the Moon.

Schmitt is the first scientist and the 12th and last person to step on the Moon. This last Apollo mission to the Moon broke several records set by previous flights, including:

- Longest crewed lunar landing flight (301 hours, 51 minutes)

- Longest total lunar surface extravehicular activities (22 hours, 4 minutes)

- The longest distance traveled in the Lunar Roving Vehicle (35 km)

- Largest lunar sample return (an estimated 115 Kg, 249 lb)

- Longest time in lunar orbit (147 hours, 48 minutes).

Post-Apollo 17 Career

In February 1973, Schmitt assumed additional duties for NASA as Chief of Scientist-Astronauts, assisting in the definition of crew responsibilities for space operations during future Space Shuttle missions.

Dr. Schmitt was appointed NASA Assistant Administrator for Energy Programs in January 1974, serving until late 1975 when he left NASA to run for election to the United States Senate from New Mexico.

Elected to the Senate in 1976, Schmitt served for six years. After leaving the Senate in 1983, Schmitt served on President Reagan’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, President Bush 41’s Commission on Ethics Law Reform, the Army Science Board, the Department of Interior’s Strategic Minerals Advisory Board, and other federal advisory entities and delegations to international meetings and elections.

Schmitt became a consultant to the Fusion Technology Institute at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1986, advising on the economic geology of lunar resources, eventually teaching in the course “Resources from Space” from 1996-2004. He remains an Associate Fellow of Engineering at the University of Wisconsin.

During NASA’s Constellation Program, Harrison Schmitt became chairman of the NASA Advisory Council in November 2005 and served until October 2008. From 2017 to 2022 he has served as a member of the National Space Council’s User Advisory Board.

Dr. Schmitt is a prolific writer, having been published in many diverse venues, including Science Magazine, Icraus, The Wall Street Journal, and the National Geographic Magazine. In 2006, Springer published his book, “Return to the Moon,” outlining a private sector approach to accessing lunar helium-3 for fusion power, medical diagnosis, and other applications. He also electronically publishes an annotated and illustrated version of the voice transcript from the Apollo 17 mission.

Active in the private aerospace business sector, Schmitt was a Director of the Orbital ATK Corporation and its predecessor company, Orbital Sciences Corporation (1983-2018). In 1990, he joined the Board of Directors of the Draper Laboratory, and,

as a retired Director, he continues as an Emeritus Member of the Corporation that oversees the Laboratory.

Dr. Schmitt continues to synthesize scientific data related to his exploration of Taurus-Littrow, including participation in NASA’s “Apollo Next Generation Sample Analysis” (ANGSA) Program, as well as consulting with NASA and private entities on issues involved with NASA’s Artemis Program to return to the Moon.

Special Honors

Schmitt has received the NASA Distinguished Public Service Medal (1982) and its NASA Distinguished Service Medal (1973) as well as nine Honorary Doctorates from the United States and foreign universities. In 2011, the American Geological Institute awarded Schmitt its Ian Campbell medal, and, in 2010, the Aerospace Division of the American Society of Civil Engineers awarded him its inaugural Columbia Medal.

Schmitt also recently received the Royal Canadian Geographical Society 2019 Gold Medal.

In recognition of Schmitt’s past service, the United States Department of State in July 2003 established the Harrison H. Schmitt

Leadership Award for Fulbright Fellowship awardees serving in the United States Military.

Additional awards include the following:

- Fulbright Fellowship in Norway (1957 to 1958)

- Johnson Space Center Superior Achievement Award (1970)

- California Institute of Technology’s Fairchild Fellow (1973-1974) and Distinguished Graduate designation (1973)

- Honorary Fellow of the Geological Society of America and the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (1973)

- United States Government’s Arthur S. Fleming Award (1973); Republic of Senegal’s National Order of the Lion (1973)

- Honorary Member of the Norwegian Geographical Society (1973)

- Honorary Fellow of The Geological Society of London (1974)

- An inductee in the International Space Hall of Fame (1977) and the Astronaut Hall of Fame (1997).

Sources

- Harrison Schmitt on Wikipedia

- Harrison H. Schmitt on the NASA website

- Apollo 17 on Wikipedia

- Harrison Hagan Schmitt’s biographical data on the NASA website [PDF]

- Troctolite 76535 on Wikipedia

- Moon Landings: All-Time List [1966-2025] - February 2, 2025

- What Is Max-Q and Why Is It Important During Rocket Launches? - January 16, 2025

- Top 10 Tallest Rockets Ever Launched [2025 Update] - January 16, 2025