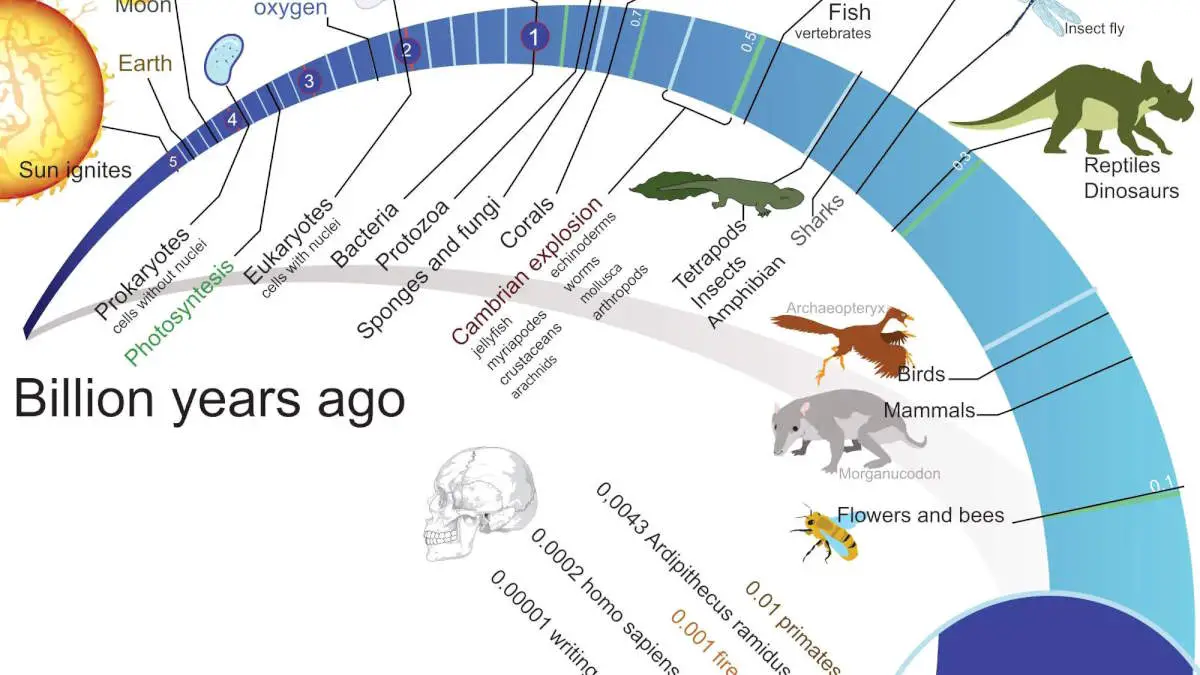

Evolution works through a process akin to a color spectrum gradually shifting from red to blue, where minute changes accumulate over time to result in significant transformations. This concept offers a vivid understanding of micro-evolution, characterized by small and subtle adjustments that are almost imperceptible on their own. Over extended periods, these incremental changes lead to macro-evolution, the broader and more noticeable shifts in species and traits. This analogy not only clarifies the evolutionary process but also helps dispel common misconceptions, illustrating the seamless and natural progression from one evolutionary state to another.